Spanish – I will say at the outset that it is not the healthiest thing for democracy: to see the military intervene in the civil political process, not even to “kindly” suggest to an authoritarian who is illegally occupying power that he should leave.

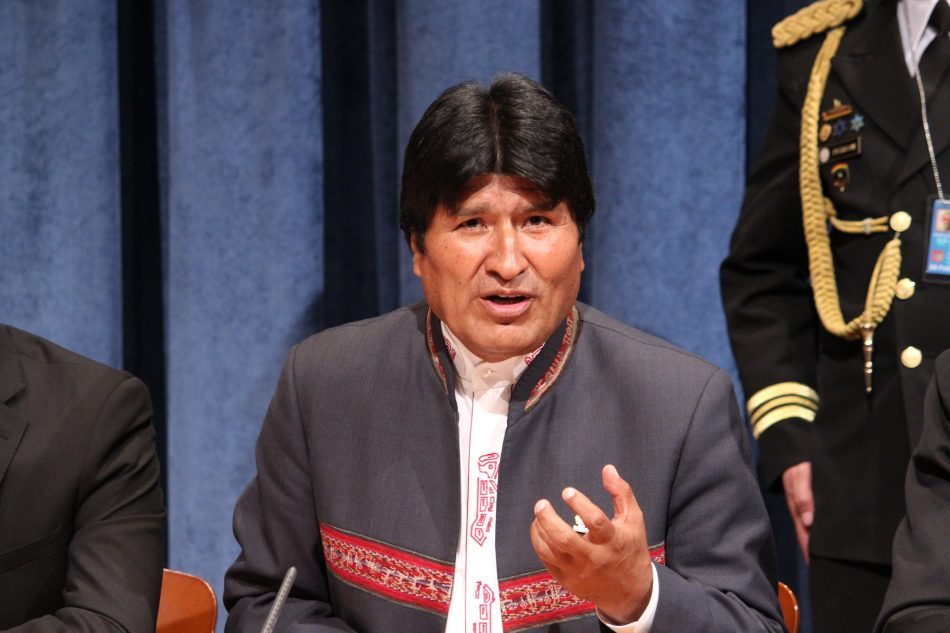

I must admit that when I contrast the situation in Bolivia with that of Venezuela, there seems to be no option. Unless the military commits to favor democracy and the rule of law, it is impossible to overthrow the tyrannical regime and prevent further atrocities. Bolivia could avoid a coup d’etat because of this precise commitment by the armed forces. What happened in Bolivia was not a coup. Evo Morales resigned from the presidency voluntarily, along with the three other people who were in the line of succession. There was no gunfire; neither did the military occupy a single building or public office. In any case, if there was a military coup, it was a coup against a coup plotter.

This situation should not prevent the interim Bolivian executive from calling new elections at the earliest. Prompt elections are a necessary measure to re-establish the constitutional order that Morales violated. Likewise, the interim administration must strictly respect the human rights of those who oppose this transition and not impose religious values. Otherwise, the new executive would just be acting like Evo Morales himself. And if that is the case, what good is the change for ordinary Bolivians?

Having said that, the events in Bolivia and the fate of Evo Morales provide valuable lessons for many Latin American countries and governments, starting with Mexico and the government of Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador.

The first lesson is that ignoring the constitution and bending legal rules inevitably leads to authoritarianism.

The governments of Venezuela, Nicaragua, that of Evo Morales in Bolivia, and others have created a presidency that is indistinguishable from authoritarianism. This is a worrying trend for Latin America. In practically all cases, international organizations and other governments were absolutely silent during these legal violations. The latest activism and follow-up by OAS in Venezuela and Bolivia should be a precedent for similar cases in the future. Those who are silent are accomplices to injustice. When international organizations remain neutral, they incentivize those administrations that were on their way to becoming tyrannies.

A second lesson: it is dangerous to go to elections with a dictator as a candidate, without an impartial electoral arbitrator.

Evo Morales’ offer to hold new elections was not only too late, but it also lacked credibility. Evo won his first presidential election in 2005. Let us remember that when he was in power, not only did he control all the organs of government and violently attack the opposition, but he also wrote and enacted a new constitution in 2009 that only allowed him another reelection (which he won in 2009, with an electoral body already under his power). Moreover, in 2014, he ran as a presidential candidate again, with an astute reading of the constitution and without any opposing power to prevent it; and he won again.

Even though the constitution placed term limits on the presidency, Morales held a national referendum in 2016 to amend the constitution and allow himself another reelection, a fourth term. He lost the referendum. Unwilling to accept defeat, he turned to the Plurinational Constitutional Court, which he controlled, to allow him to participate again in 2019. As expected, the court unanimously approved his request to run for office for the fourth consecutive time.

The results of the 20th October elections indicated a victory for Morales. However, international election observers invited by Morales’ government as well as the company invited by the regime to audit the election confirmed that there were serious discrepancies. If Morales ran as president again with the same judicial bodies, he would definitely repeat the electoral fraud. That is why it was imperative that he resigned and did not just hold new elections. Term limits should be a requirement in countries such as Venezuela, Nicaragua, and Cuba if they ever have free and fair elections with neutral and independent electoral bodies.

Third lesson: people will get tired when the rulers regularly abuse them. They will rebel and end up appealing to the military.

Evo believed himself to be the savior, so he changed the rules, time and again, at his whim, to maintain power for 14 consecutive years, and seized control of all institutions. From a position of power, he attacked politicians, entrepreneurs, the army, opposition indigenous communities, the catholic church, journalists. He persecuted them judicially, violently assaulted them, unjustly expropriated companies and lands, and fabricated attempts against his life. Now, after almost three terms of aggressions and violations, the attacked people rebel, but instead of accepting their mistakes, Evo dismisses their frustrations as a coup d’etat!

The lack of balance and counterweights makes matters worse for society and increases polarization. The lack of institutions that serve as a balance to contribute to a political and constitutional solution to the significant problem of a democracy, who must command, forced the ominous (but necessary) intervention of the military. The security forces show that they are the only institutions that can stop the populist tyrants. The authoritarian rulers, like Morales, who are hungry for power, start with a discourse of love for the people and soon tear apart laws, constitutions, and institutions. If you don’t want that way out, you have to start by not abusing power.

A fourth lesson is to assume that co-opting and destroying institutions of control (electoral, financial, human rights, and so on) ultimately goes against the government itself.

A government that destroys the independence of all public institutions digs its own grave, in the long run. It ends up in a place where all problems reach the executive and are counted against it; therefore, it ends up without credibility, fighting with everyone. In Bolivia, all the institutions were quashed as intermediaries and counterweights because they were in the service of Morales, and those who were in charge of those institutions became mere subordinates of Evo. Bolivia shows that the balances are essential, and the performance of the counterweights is fundamental if we do not want to generate a situation of ungovernability.

And finally, the fifth lesson: the submission of all state institutions to presidential power and its accomplices impedes the conditions to ensure and give permanence to political, economic, and social change instead of strengthening the autonomy and professionalism of the institutions.

Those who bet on the annihilation of institutions to supposedly strengthen and concentrate their power actually build their fleeting passage through it: in the end, there will be no institutions over which a new country can be built, and their influence will last as long as the biological existence of the dictator. Co-opting and destroying institutions goes against any project of permanent change. The important thing is that from the ephemeral passage of a charismatic leader to military intervention if we want to avoid greater chaos, there is only one step. This is what we see today in Bolivia.

Bolivia is an excellent example; the government of Mexico and other countries should reflect on it to avoid walking the same path as Evo Morales (which was that of servitude, illegality, abuse, polarization, institutional destruction) to avoid ending up like him and like Bolivia.

Versión Español

Versión Español