EspañolMore than a month later, Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro has yet to unveil the details of the “economic overhaul” he announced would address the nation’s current crisis. Meanwhile, the black-market exchange rate of bolívares for US dollars continues to climb.

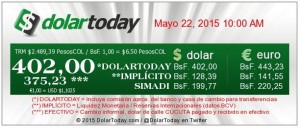

On Thursday, May 21, the exchange rate broke the 400 Bs. per dollar mark for the first time, meaning Venezuelans living on the minimum wage are left earning only US$16.80 per month.

The unofficial rate — 422.5 Bs. per dollar at press time — is now 67 times higher than the lowest fixed rate set by the government’s foreign-exchange controls put in pace over 12 years ago on February 5, 2003.

The black-market exchange rate is calculated by the website DolarToday, which reports the value of the foreign currency in Venezuela based on daily exchange operations in Cúcuta, a Colombian city near the southern border.

Reactions were immediate and the hashtag #400Bs became a worldwide trending topic on Twitter on Thursday evening.

El dolar pulverizado por @NicolasMaduro supero la barrera de los 400bs/$… ahora se enfila a los 500! Bravo Nicolas! eres grande

— Guevara (@ManuelGuevaraB) May 22, 2015

“The bolívar, smashed by @NicolasMaduro, has surpassed the 400 Bs./US$1 barrier… and is now heading toward the 500 Bs.! Bravo Nicolás! You’re awesome.”

400 Bs por dólar no es un punto de llegada. Es una meta volante. La idea es que mendiguemos aún más al Estado.

— LCD (@LuisCarlos) May 22, 2015

“400 Bs. per dollar is not the end. It’s a starting point. The idea is that we beg the state even more.”

In just eight days, the exchange rate went from 301.93 Bs. to 402 Bs. on the black market, where Venezuelans must purchase their dollars when unable to obtain the tightly controlled lower-rate currency from the government.

Venezuelan consumers are feeling the adjustment. As it becomes increasingly difficult for companies to acquire low-rate dollars, the black-market rate functions as an important signal for setting prices and buying products.

Venezuela’s official foreign-exchange market has three rates, which in practice almost no citizen can access. The national government decides who gets these scarce dollars and when.

The lowest rate, the CENCOEX, is set at 6.30 Bs. per dollar, and is reserved for companies that import basic foodstuffs and medicine. The second rate, SICAD, stands at 11 Bs. per dollar, and is doled out to firms that import non-essential items and travelers. Lastly, the SIMADI rate for the general public nears 200 Bs. per dollar and relies on the availability of local exchanges.

Both SIMADI and SICAD have come under fire over the small amount of dollars they allow Venezuelans to buy, which has prevented companies from paying off the billions of dollars of debt incurred with their international suppliers since 2013. The inability to settle these debts has caused a massive shortage of basic products in the country and an official cumulative inflation rate of 68.5 percent for 2014.

Calculating the Unofficial Rate

DolarToday calculates the unofficial price for dollars in Venezuela based on the way bolívares are trading for Colombian pesos in the neighboring city of Cúcuta. Experts believe this is a proxy that best reflects real supply and demand for dollars in Venezuela.

Businesses then take DolarToday’s rate as a signal of the dollar’s true value in Venezuela and price their products and services accordingly.

Why the Big Jump?

Economist Francisco Faraco told the PanAm Post that the increased demand for the unofficial dollar results from the government’s tight control of the currency, which it reserves for “entities that the state deems a priority.” Until more dollars are made available through official means, Venezuelans will seek to preserve their money in a stronger currency on the black market, he explained.

Faraco argues the black-market dollar rate has shot up drastically because the Venezuelan government operates a “hugely irresponsible economic policy, which translates to a fiscal deficit and worthless money being printed.”

He says the excess bolívares in circulation compels the public to try and protect their savings by converting it into dollars.

The economist Luis Oliveros also explained to the PanAm Post that the unofficial dollar’s rise could be seen as a reflection of the unease among Venezuelans, exacerbated by their expectations on inflation. The public no longer wants bolívares because they are worth less with each passing day, he argues.

Oliveros believes the Maduro administration has not demonstrated any intention to improve the country’s economic crisis. “It seems inflation will reach three digits in 2015, and the price and exchange controls will continue; this signals bad news and pessimism among the population,” he predicts.

Misguided Economic Policies

Faraco says Venezuela’s crisis can be attributed to the misguided economic policies Maduro inherited from the Chávez administration. Over the course of 15 years, the Venezuelan government failed to take advantage of the highest oil prices in history, he laments.

“We didn’t do much with the oil bonanza. The government thought those US$100 per barrel would last forever. It did not encourage private production, as it thought it could expropriate our way into prosperity, and today we’re all paying for that,” Oliveros added.

Both experts agree the government should begin by dismantling its crippling controls, and work with the private sector to resume production. Instead, Maduro continues to “incentivize the problems to persist,” they say.

On Tuesday, May 19, Maduro announced he would soon release the details of the “economic overhaul” promised in late April. The reforms are expected to be passed through an Enabling Law, which will not require congressional approval.

Maduro claims the reforms are designed to “put a stop to the smuggling of basic products and the plundering oligarchy.”

Versión Español

Versión Español