EspañolIf Latin-American history has shown us anything, it is the ambition of leaders new and old to rewrite the rules of the game and reinvent the institutions that brought them to power. This inevitable characteristic plagues the so-called democracies of the region, as rulers alter national constitutions on a whim and leave the rule of law ruptured in their wake.

Honduras has been one of four countries in Latin America with an absolute prohibition on presidential reelection, along with Guatemala, Mexico, and Paraguay. Her constitution establishes time limits on the duration of presidential terms, precisely to protect and guarantee the republican principle of alternation in the exercise of public office.

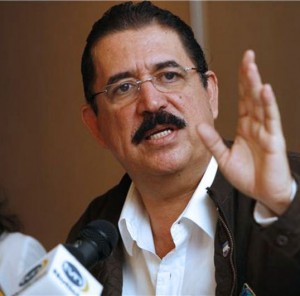

In 2009, the military deposed then-President Manuel Zelaya and exiled him to Costa Rica, marking the first military coup d’etat of the 21st century in Latin America, after the third wave of democratization in the 1980s and 1990s. One of the allegations leveled at Zelaya was that he had violated the constitutional principle of non-reelection, as he sought to extend the Venezuelan project of 21st-century socialism to Honduras.

Current Honduran President Juan Orlando Hernández supported Zelaya’s removal at the time, arguing that “you can’t touch the Constitution,” and that Zelaya intended to keep himself in power. Now, as the head of the country and apparently suffering from a grave case of amnesia, Hernández is set to replicate the practices of regimes in Venezuela and Nicaragua that he once considered anti-democratic.

On Tuesday, April 22, the Constitutional Chamber of the Supreme Court of Justice (illegally appointed by Hernández) approved a constitutional reform that allowed presidential reelection. After 33 years, and through unorthodox and illegitimate methods — it should have been Congress or citizens via a referendum that authorized such a change — those in government have been able to change the articles “carved in stone” by the 1982 Constituent Assembly, the year in which Honduras returned to democracy.

The assembly members of 1982 made clear in the Constitution the illegality of reelection. They wanted to ensure that the institutions of the country were governed by civilians, and not by the same military caudillos who had held power for extended periods ever since independence, and violated successive constitutions at will.

Claiming that the Constitution is unconstitutional might seem like an allusion to the magical realism of Gabriel García Márquez.

The principle of alternation, through term limits, was so emphasized in the Constitution that up until last week it was considered treason for the president to seek reelection, as per Article four. Article 239, moreover, established that those found guilty of seeking to extend their stay in office would be barred from political power of any kind for 10 years.

Last Tuesday’s ruling was in response to two challenges to the Constitution. The first claim was filed by a group of congressmen, asking for the second paragraph of Article 239 to be scrapped on grounds of unconstitutionality. Claiming that the Constitution is unconstitutional might seem like an allusion to the magical realism of Gabriel García Márquez, but a second challenge was quick to follow: this one by former Honduran President Rafael Leonardo Callejas (1990-1994), who asked for Article 239 to be revoked in its entirety.

The Constitutional Chamber in turn issued the same sentence in response to both petitions. They decreed the inapplicability of Articles 239 and 240 of the Constitution, which formerly made it a crime to seek presidential reelection.

The irony of Latin-American politics is always heavy handed. It was the same attempt at “manipulation” of the apparently unchangeable articles of the Honduran Magna Carta that provoked the 2009 political crisis and Zelaya’s consequent removal.

The difference, by contrast, is that Zelaya sought to refer to a popular referendum that would ask citizens their opinion, and not even about presidential reelection outright. Instead, the poll was to determine whether they agreed with a fourth ballot box at the following presidential elections, which would then allow them to vote on whether or not they wanted reelection.

With this illegal isolation of Zelaya as a democratically elected president, it’s clear that a break with the rule of law occurred, leading to a polarized society and over-concentrated power in the executive.

These problems added to a culture of impunity, in which uncontrollable levels of violence and insecurity are the order of the day, and continue to weaken already-fragile state institutions. The solution of Hernández’s government, in the face of this calamitous situation, has been to militarize the country, leading to an increase in complaints of human-rights violations without any improvement in security.

In such trying conditions, how could the massive waves of illegal migration towards the United States, including unaccompanied minors, fail to continue? Instead of focusing on crucial issues for the functioning of democracy and society, like eradicating poverty, promoting investment, and improving infrastructure and public services, the Honduran political class opt for tinkering with the Constitution, manipulating its laws according to their fancy, and twisting the very notion of democracy out of all recognition in the process.

Thus the political interests of a caudillo‘s regime prevail once again over the republican, liberal, and democratic institutions through which power should be transferred peacefully between rulers.

We already know too well the fatal outcome in those Latin-American countries whose leaders have violated laws at their discretion do keep themselves in power.

Where did the ferocity of those who opposed reelection in 2009 go? Did the terror of indefinite presidential rule that led half the population to oppose Zelaya and plot against him, overthrowing him through a military coup, disappear?

While Zelaya’s intentions were pernicious and equally disrespectful of the rule of law, steps were taken to confront him (albeit equally unconstitutional and incorrect) and there was at least a popular mobilization by civil society and the opposition (albeit repressed) in defense of the constitution. The situation now is the same or even worse, but Honduran public opinion is demonstrating an alarming silence before a situation that puts democracy itself at risk.

To try and generate some reflection in these times of unrest, little could be more appropriate than the words of the liberator Simón Bolívar in his Message to the Congress of Angostura:

Nothing is more dangerous than letting the same citizen remain in power for a long time. The people become accustomed to obeying him, and he becomes accustomed to ordering them; from which usurpation and tyranny originate.

We already know too well the fatal outcome in those Latin-American countries whose leaders have violated laws at their discretion do keep themselves in power. It seems as though Honduras is set to join the chorus of nations under authoritarian “democracies,” and take her place alongside such fine role models as Nicaragua, Bolivia, Ecuador, and Venezuela.

Translated by Laurie Blair. Edited by Fergus Hodgson. Update: 3 p.m. EDT, April 28, 2015.

Versión Español

Versión Español