EspañolIn a world where high inflation is no longer a problem, Argentina’s inflation is still the population’s main concern. Only Spain and Venezuela show inflation rates above 20%, with the principle concern being that this trend has continued for more than ten years.

For this reason, and in parallel with the completion of the new government’s first three months, the Buenos Aires economic newspaper El Cronista Comercial asked expert analysts to offer their opinion and advice on how to lower inflation.

While among this analysts we can find accurate points of view related to budgetary imbalance and uncontrolled monetary emissions that deteriorate the currency’s purchasing power, the fact remains that among their “advice” are lots of misdiagnoses, followed by absurd proposals.

Economist Augustine D’Atellis, a member of the “GraN MaKro” group (N and K are capitalized in honor of former Argentine President Nestor Kirchner), suggested that:

“… Market freedom in price formation leads to increasing inflationary dynamics, to the detriment of the wages’ purchasing power.”

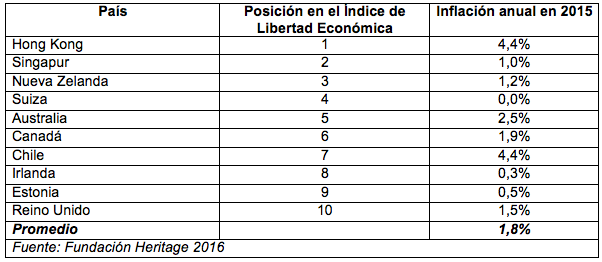

But this statement is clearly false. In the table below you can see the world’s economically freest countries. That is, those where D’Atellis said the free market “forms prices.”

What his “analysis” recommended is the opposite of true. Where there is a free market, inflation is not high, but considerably reduced — with an annual average of 1.8 percent. That is, no less than 94 percent lower than what Argentina had in the same year.

Therefore, inflation has nothing to do with the free market.

Another person who gave his opinion was public accountant, congressman and former Economic Policy Secretary Roberto Feletti.

“The effective anti-inflationary policy is one that combines market regulation, essentially in those monopolistic supplied goods and rigid demand, and with price and wage agreements,” he said.

The problem with this analysis is that it confuses inflation with the high prices placed by a company. That is, if a monopoly sets a price of US $100 for its product, but that price is kept for 10 years, does it really have to do with inflation? Since it is a monopoly, we can probably agree the price will be high, but high prices are not the same as inflation, so price control over monopolies is by no means an “anti-inflationary policy.”

Mercedes Marco del Pont, former President of the Argentina Central Bank between 2010 and 2013, said “the Central Bank’s decision to minimize interventions [in the foreign exchange market] in order to promote the free float does not seem consistent with its objective of controlling inflation.”

According to this view, a type of free trade and market defined by the Central Bank with inflation-targeting is a bad idea. However, it is what a lot of countries in the region such as Peru, Colombia, Chile and even Brazil have done.

In all these countries, the monetary authority left the exchange rate float. And to the surprise of Marco del Pont, they hold a free exchange rate with very low inflation compared to that of Argentina or Venezuela, who opted for exchange control as an anti-inflationary strategy.

Misdiagnoses as to the inflationary phenomenon abound in our country. The fault falls on business traders, the free market or the the dollar. Elements such as an overwhelming public spending or frenzied monetary emission should never be part of these specialist analyses.

No wonder, then, that, in providing answers, they advise to do everything that has already failed on multiple occasions in the past.

That leaves us with one thing to make clear: if we follow their prescriptions, we will repeat past mistakes and, even worse, not lower inflation. The best thing the new government can do is turn a deaf ear to such recommendations.

Versión Español

Versión Español