Spanish – We had not walked more than forty meters from his apartment when a young African-American man, with noble gestures and a tasteful dressing sense, took off his hat to bow and say, “Mr. Ambassador, hope you have a nice day!”

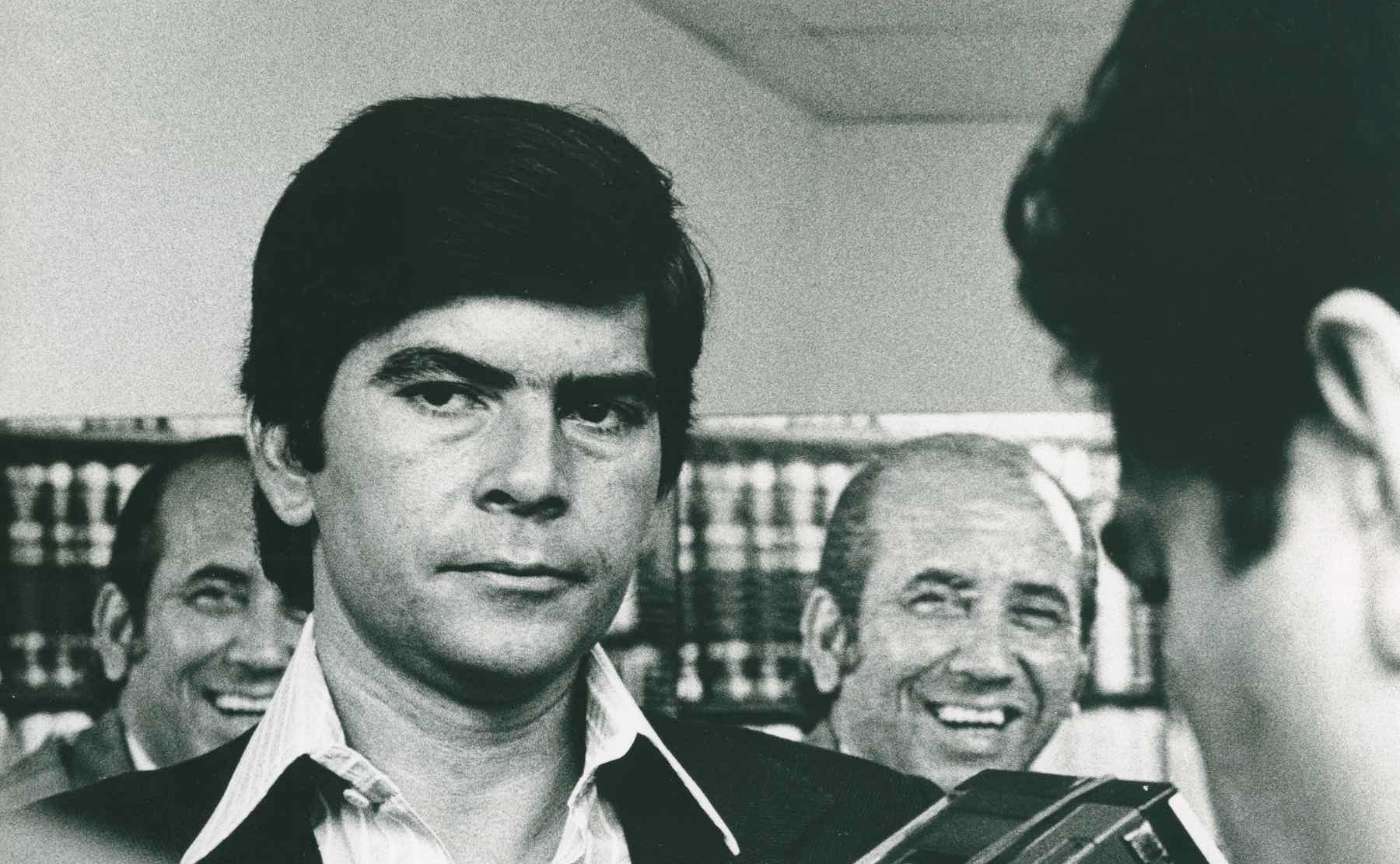

Diego Arria did not accidentally become Mr. ambassador, the one who deserves reverence and the customary greetings of your excellency. Tempered among the Caracas elites, he always stood out for his sharpness, intellect, and an almost naive idealistic spirit, which still led him to believe that we were not the first world, we never had been, but we could reach there.

Aiming to make Venezuela a first-world nation is as silly as taking Eugene Ionesco’s works to Caracas or showing a Fellini movie in a Plaza Venezuela movie theater and trying to get rich off it. It’s wanting and asking too much. You are expecting too much from a country that has always preferred the soap operas (tragic and comic) of some mediocre Venezuelan writer and commentator, or just gone to the movies to see drugs, kidnappings, gunshots, or some bad and crude comedian playing James Bond.

Moreover, it’s not that the other countries are different. It’s not that in the first world they opt for Dostoyevski instead of some self-help writer. No. But always think about improving, about becoming an informed nation, a nation. Also, that this nation is competent, skillful, well-versed, well-informed, cultured, knowledgeable, and not foolish, will always seem like the idea of romantics, sentimentalists, and dreamers.

But Arria always dreamed. In 1978, when he was only forty years old and had been a member of parliament, governor of Caracas, president of the Simon Bolivar Center and Minister of Information and Tourism, Arria wrote in his book, Primero la Gente, or People First:

“What will Venezuela be like five, ten, fifteen years from now? What country will reach the 21st century? Many find it hard to think in these terms. They imagine, for example, that the 21st century is as distant in the future as 23rd January 1968, is in the past. In just 22 more years, we will have reached the year 2000.

Not only the future of our children and grandchildren but also our immediate future depends on whether we begin to focus on our problems from that perspective.

Today, Venezuela has a unique opportunity that no other developing country has at its disposal: it has managed to muster the political freedom and material resources necessary to transform its economy and its social structure. Most developing countries lack both: some have freedom without resources, and fewer still have resources without liberty.

This privilege of Venezuela is, however, a conditional privilege: if we know how to use it, we will build a modern democracy. We will develop a balanced, productive structure and disseminate social welfare. Thus, we will reach the twenty-first century as one of the most consequential and stable countries, with minimum problems and maximum social satisfaction.”

Nations will always regret that their great men are treasured around the world but not in their birth countries. A historical complexity manifested in that biblical saying “no one is a prophet in his own land.” The Venezuelan lawyer Jose Ignacio Hernandez, visiting fellow at Harvard University and now the attorney general of the interim administration of Juan Guaido used the simile, “today, Diego Arria is our Francisco de Miranda.” It is accurate, and he intended to make it clear to me that there is no other internationally-known Venezuelan today who has commanded more battles in distant lands than Arria.

But on the other hand, we all know about Miranda’s great tragedy. A story with Greek traits that obliges many to reflect on Venezuelan-ness and our ancestral habit of plunging daggers while we also make great strides. One step, a dagger!

In 1978 he said so, and no one heard him. That’s why he didn’t win the presidential elections that year and Venezuelans preferred to stick with the man who seemed sensible but also let himself be captivated by the almost unlimited flow of cash.

Similar to the most modern civilizations, more prepared, more posh, and more well-versed, Arria was responsible for founding the Caracas Daily and the Foundation for Culture and the Arts, both projects that involved Anglo-Saxon characteristics. An economist trained in Michigan and London, Diego Arria developed an outstanding career at the Inter-American Development Bank that allowed him to stand out among the nobility and fine people of Washington.

In fact, Arria even joined Carlos Andres Perez after the famous American advisor, Joseph Napolitan, who had led Kennedy to the presidency, suggested him as an essential contribution to the Venezuelan president’s team. Arria and Perez would maintain a friendship that would last for the rest of the latter’s life and gain him antipathies within a party plagued with feelings of inadequacy.

But the point is, besides Perez, nobody heard him in Venezuela. The whole country ignored him. Fortunately, the head of state, already a man of the world in his second presidency, understood the universal value of Diego Arria and his particular ability to understand countries and their conflicts. By taking him to the United Nations as ambassador in 1991, he put the best Spanish bullfighter in Barcelona’s Plaza Monumental. Invincible.

Arria went from being the mere representative of a Caribbean nation to leading Venezuela’s international efforts to have an impact on the world. As an ambassador, he managed to turn his country into an important actor in the most prestigious quadrilateral of diplomacy. He managed to move astutely through the involuted corridors in New York, and his voice began to be not only heard but also obeyed.

He was president of the United Nations Security Council and played a leading role in resolving the Yugoslav conflict of the 1990s. He was an advisor and assistant secretary-general to Kofi Annan, the seventh secretary-general of the United Nations. He helped to build the principle of Responsibility to Protect and today, a United Nations dialogue mechanism bears his last name: the “Arria Formula.”

“I presided over the UN Security Council, and the conflict in the Balkans was ongoing. At that time, the main victims of the conflict, the Bosnian Muslims, did not have direct access to the Security Council. It was very frustrating. The first meeting we had under what is now known as the Arria Formula was a coffee that several of the Council’s ambassadors had with a Croatian priest,” Arria once told me at a restaurant in New York.

The Formula, which has served as a mechanism for resolving conflicts as tense as apartheid in Africa, turned Diego Arria into a walking institution. He walks, and when he sets foot in the United Nations building in New York, officials raise their hands to their foreheads and march steadfastly.

The International Criminal Court owes part of its existence to him and Serbian tyrant Slobodan Miloševic, his conviction, in large part.

I know I’m missing experiences, anecdotes, and posts. There is no Venezuelan with a resume similar to that of Diego Arria. Jose Ignacio Hernandez is right when he calls him Francisco de Miranda. Marshal of other people’s battles. One day we will celebrate him in his Caracas as they honor him in Madrid, Paris, New York, or Washington. Not today. At least not by those who rule. Because on one side, the left, they persecute him, and on the other side, they feel uncomfortable.

At the last minute, after months of postponing the decision, the legitimate President Juan Guaido appointed Miguel Pizarro as Venezuela’s representative to the United Nations and its General Assembly. He is a very young representative who is neither an expert nor has any other merit than that of having been voted for in a setting in which people did not even know the name of the person they supported.

Not inviting Diego Arria to be part of the interim government in the quixotic endeavor to achieve recognition from an organization that does not recognize us, has been a very damaging mistake. Now, the Arria institution will not arrive in New York to represent Venezuela. Instead, there will be a young representative without a lucrative resume, and he has the reputation of being a communist.

The tricks, when they’re bad, they’re contagious. So this interim government suffers from the same Chavismo virus. Because just as the regime appoints military personnel to control oil production, the Popular Will party appoints inexperienced communicators to the world’s largest diplomatic ring.

It was a mistake to neglect the United Nations for so many months. But it is worse, a thousand times worse, to underestimate that battlefield.

**

We had not strayed three blocks from the elegant African-American man when, as we entered an Italian restaurant, a distinguished gentleman opened the door and said, “Welcome again, Mr. Ambassador! We were expecting you, Sir!”

Diego Arria will continue to be honored in the world as Mr. Ambassador. Pizarro will have to start earning it. Let’s hope that, meanwhile, he has the humility to ask the matadors for advice because they have been fighting bulls for decades in the arenas of Barcelona and the world.

Versión Español

Versión Español