Español “In a state of emergency” were the words used by prominent Venezuelan newspaper El Universal when it announced that it could only circulate for another two more weeks, due to a paper shortage. In an article released yesterday, the newspaper points to the newly created National Center for Foreign Trade (CENCOEX) — a government agency in charge of approving Venezuelans’ access to foreign currency — as the one to blame.

In recent months, CENCOEX’s bureaucratic obstacles have made paper almost impossible to import; the foreign currency red tape has been a problem not only for El Universal, but for the many other newspapers in the country.

“The unbelievable delay in the authorization to acquire foreign currency.… hasn’t allowed us to import a shipment of paper … which is necessary for daily operations, and has forced the urgent decision to ration more of the main supply for the printed media,” the article states. The newspaper reduced its supply by more than 30 percent, so that it could extend its scarce provisions for two more weeks.

Unfortunately, El Universal is not the first one to suffer a paper shortage. According to Espacio Público — an NGO that advocates for the rights of journalists and freedom of speech in Venezuela — between August 2013 and January 2014, approximately 10 newspapers have had to shut down because of paper shortages, and others have organized rallies and protests to demand a response from the authorities and a solution.

The president of the National Assembly, Diosdado Cabello, has flatly denied that such a paper shortage exists in Venezuela. Instead, he has denounced the presence of 13,700 reels of newsprint at port La Guaira that “haven’t been picked up” by the owners.

“Who bought it? Who brought it? Why hasn’t anyone picked it up from the port?” the Chavista representative asked, and he suggested that complaints were all a plot to create a matrix of opinion about an alleged paper shortage.

What Cabello leaves out, however, is the reason behind the “abandoned” reels of paper. According to El Universal, since January, the paper is in fact at customs in port La Guaira, waiting for CENCOEX to finally approve its payment in foreign currency. While the government body has taken almost five months to proceed, El Universal has had to consume its final paper reserves in order to survive.

Other notable newspapers, such as El Nacional, El Nuevo Pais, and El Impulso have had to resort to the media from neighbor country Colombia. The Colombian Association of Newspaper and News Media Editors agreed to lend these three Venezuelan newspapers 52 tons of paper to help them to keep up with the circulation for the next few months.

Carlos Correa, executive director of Espacio Público, spoke exclusively with the PanAm Post about the newsprint shortage. The problem is no longer solely economic, it’s also a political one, explains Correa: “the government is aware that the economic crisis is affecting the media’s imports of newsprint. Newspapers have had to reduce the number of employed journalists, and this, without a doubt, has acquired a political nature.”

The reality for state media, on the other hand, is quite different, according to Correa. Paper shortages are not a problem for state media, or other newspapers whose editorial lines are aligned with the government’s platform: “they import their paper without any difficulties.… It’s clear there is a political bias in this shortage,” Correa affirms.

Claudio Paolillo, president from the Free Press and Information Commission of the Inter-American Press Association, describes the situation as not about economic restrictions, but as a new form of censorship. The Venezuelan government continues to wait for “newspapers to shut down, with the subtle measure of denying them access to foreign currency so that they can no longer import paper and other supplies that aren’t produced in the country,” states Paolillo.

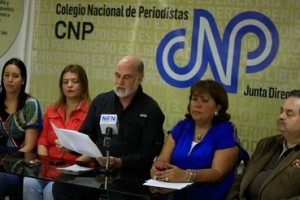

Last Thursday marked Labor Day, and the president of the National Association of Journalists (CNP), Tinedo Guía, informed the public that so far the board of directors of the CNP and the National Union of Press Workers, were still waiting for a response from the Ombudsman and the National Assembly.

“Not even one written communication from the government in the face of this concerning lack of paper. This clearly shows how they insist on silencing the news that big newspapers publish throughout the country,” Guía stated.

According to the president of the CNP, press freedom is weakened and is severely jeopardized in Venezuela: “the refusal from CENCOEX to allow newspapers to convert their bolívares [Venezuelan currency] into dollars for the importation of paper and other supplies has condemned important media to silence…. This translates into less information and less space for knowledge.”

Versión Español

Versión Español