EspañolIn the same week that Pope Francis published his encyclical rejecting capitalism and its progress, Ecuadorian President Rafael Correa announced new taxes on wealth and inheritance, and the United Nations finally acknowledged the failure of Venezuela’s Bolivarian model. How can we explain these three events?

Initially, I planned to take the easy way out, and blame it all on the supposed Latin-American mindset that the state can and must take care of everything, even at the expense of individual freedom. I intended to write that Latin America is the only region where these socialist ideas persist, despite their disastrous consequences (just look at Venezuela).

I was also going to suggest this is one of the few regions in the world where countries have actually adopted the highly questionable proposals that Thomas Piketty recommends in his bestseller, Capital in the Twenty-First Century, regarding the punitive taxation of wealth and inheritances.

To explain this alleged mentality, I thought of holding certain Latin-American intellectuals responsible, like Fernando Henrique Cardoso and Enzo Faletto, or Eduardo Galeano. After all, these scholars were responsible for turning the outsourcing of blame into a sort of academic theory: the idea that poverty in Latin American exists because of the rich, just because they’re rich.

I planned to conclude my argument with a contradiction: if there was ever a society that should be reluctant to statist solutions and support individual freedom, it should be Latin America. After all, this is where the most salient cases of state failure occur.

What’s more, the suffering that the legitimization of the state’s excesses causes is evident. Shouldn’t that be the lesson of the region’s many past dictatorships? Furthermore, it is a region where individuals suffer various sorts of wealth confiscation to this very day, corruption being one of the most cruel and shameless forms.

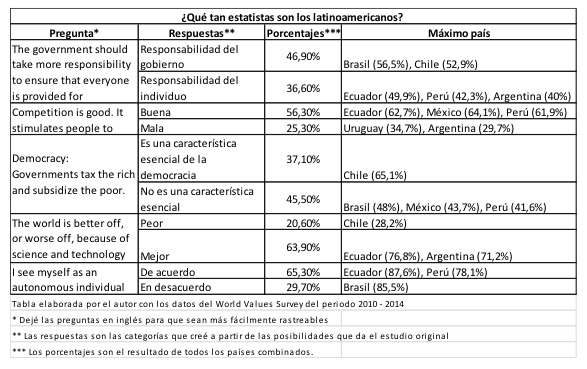

However, when I contrasted what I believed with the data, things looked quite different. After reviewing the World Values Survey, I found another reality.

There are only eight Latin-American countries in the survey: Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, Mexico, Peru, and Uruguay.

I did not check all the questions, but only those that allowed me to show the respondents’ position on statist ideas. Then, I grouped the questions into these categories:

What this table mainly shows is that I was wrong. There is no such thing as a Latin-American statist mentality. Latin Americans believe in competition; they believe that technology has been positive for humanity, and they value autonomy. The only hint of statism is the idea that the state should do more to guarantee all citizens a basic minimum threshold, a belief that is debated within liberalism as well.

The most alarming responses I discovered came from Chile. Could it be that Chileans are tired of being the most developed country in Latin America? The answers coming from Brazilians were also quite troubling. Based on the survey, Brazil appears to be one of the most statist societies in Latin America. Peru, however, brings good news, but the real surprises are Ecuador and, to a lesser extent, Argentina.

Therefore, the real paradox is twofold: on the one hand, there is an apparent disconnect between what Latin-American governments do, and what their citizens think they should do. In other words, Latin-American governments are not representing the will of the people (except for Brazil, which has had statist governments desired by statist people, and Peru, which has managed to stay on a path of timid liberalization).

On the other hand, it appears that the countries that have suffered the worst hardships of big government, like Ecuador and Argentina, value and yearn for freedom the most.

Therefore, the idea of a statist mentality prevailing in Latin America is not supported by the evidence. Rather, what we are facing is a cruel and open statist oppression by social leaders — be it the pope, Rafael Correa, or the Chavistas — imposing their minority worldview on the rest of the public.

We are, however, in danger of losing sight of the ideas that made Chile the prosperous country that it is today. Ultimately, there is an emerging opportunity for the various liberty movements across the region to have an impact, and the conditions are set for them to thrive.

Versión Español

Versión Español