EspañolNew poverty statistics were recently released in Argentina revealing that three out of every 10 Argentines are poor.

The Catholic University of Argentina, which in the absence of a credible national index provider, took on the role for the last 10 years, disclosed this new estimate and the harsh reality of the country’s situation.

The recently revealed data represents an increase of almost four points compared to last year and is the highest recorded poverty rate of the last 11 years. A real social catastrophe.

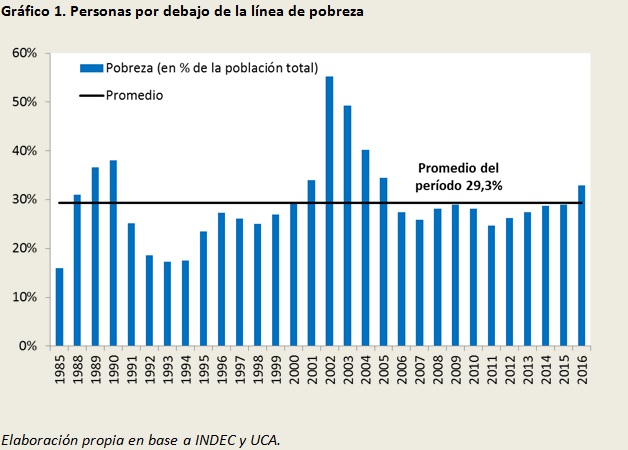

Looking at the numbers in the longer term, we find that since the return of democracy, average poverty in the country hovered around 29.3 percent. In addition, we also find that the number of poor people does not show a downward trend (as it does in most of the world), but fluctuates around the average, with sudden increases.

How is this possible?

(Chart 1. People under the poverty line)

To understand why there are 13 million people in poverty in Argentina, we have to look at why these sudden leaps prevent the situation from improving over time.

Poverty exceeded 30 percent between 1988-1990, between 2001 and 2005 as well as in 2016, showing that strong increases in poverty in Argentina are directly related to the economic crises that the country often has. And what was the common element in these economic crises? The inflationary outbreak, which caused prices to rise higher than peoples’ incomes.

- Read More: Colombian Senator Demands President Santos Resign in Wake of Odebrecht Scandal

- Read More: Ex-President of Peru Garcia Linked to Metro Corruption Case Involving Odebrecht

In 1989, the populist model of Raúl Alfonsín collapsed. After decades of chronic inflation, monetary issuance grew at unsustainable levels and prices rose. In fact, the annual inflation rate ballooned by 20,000 percent annually. The economy collapsed and poverty doubled from year to year.

In 2002, prices climbed 40 percent while revenues remained practically static. The result was a brutal jump of 20 points in the poverty rate.

The same thing happened in 2016. Inflation in the city of Buenos Aires marked an increase of 41 percent per year, while wages did not grow beyond 30 percent.

There is a direct relationship between inflation and poverty, so everything that goes in the direction of ending inflation will clearly help improve the situation.

But the most important question to answer is what and who is responsible for inflation. This, the fiscal deficit and the politicians who spend more than what they have are the root of the problem.

The fiscal deficit causes inflation because, to finance the imbalance of public accounts, the Central Bank spends excess money that results in the loss of significant purchasing power. At the end of the convertibility period, the relationship was not so direct, but it was the deficit that made convertibility unsustainable, and that was what gave rise to an inflationary outburst.

Unlike what happens in the world as a whole, poverty in Argentina is increasing and, on average, has not declined from 29 percent in 32 years. Now, contrary to what many would have us believe, this situation is not related to the implementation of “neoliberal policies,” but to something very different.

It is the government, with its demagogic plans, that causes the fiscal deficit. And it is the deficit that, in the long run, ends up causing economic crises with inflationary outbursts.

True economic liberalism demands a lesser role for the government and zero public deficit. If that prescription had been followed in our country, we would have saved at least three economic crises.

In light of this data, it should be clear that the only ones responsible for poverty are those promoting statism, and that the only way to turn the page on this black moment in Argentine history is to reject those policies once and for all.

Versión Español

Versión Español