One lesson from the Bolivian crisis is that the institution of suffrage is alive and well in Latin America. The region indeed has a high level of tolerance for the tricks used to perpetuate power, including indefinite re-election as Evo Morales. However, all leadership must be revalidated at the polls.

No society welcomes this perpetuation. The indispensable chimeric leader has to win “free, fair, and transparent” elections. Electoral fraud activates the antibodies of Latin American democracy.

Thus, when Evo Morales proclaimed his victory on the night of 20th October – precisely by stealing the election – he was becoming a usurper of power. So much so that he could not even fulfill his current constitutional term. It is the age-old theme of the legitimacy of origin.

This takes us to Venezuela. When Maduro swindled the 20th May 2018 election, he received unanimous repudiation. The fraud was documented by Smartmatic, the company that processed the data and demonstrated that the official results were inflated. The “winner” had been abstention.

Hence, the Venezuelan National Assembly and the legitimate Supreme Court, both elected per the terms of the constitution, declared the elections null and void. So did most of the democratic nations and the OAS, whose General Assembly issued a resolution on 5th June 2018 disavowing that election.

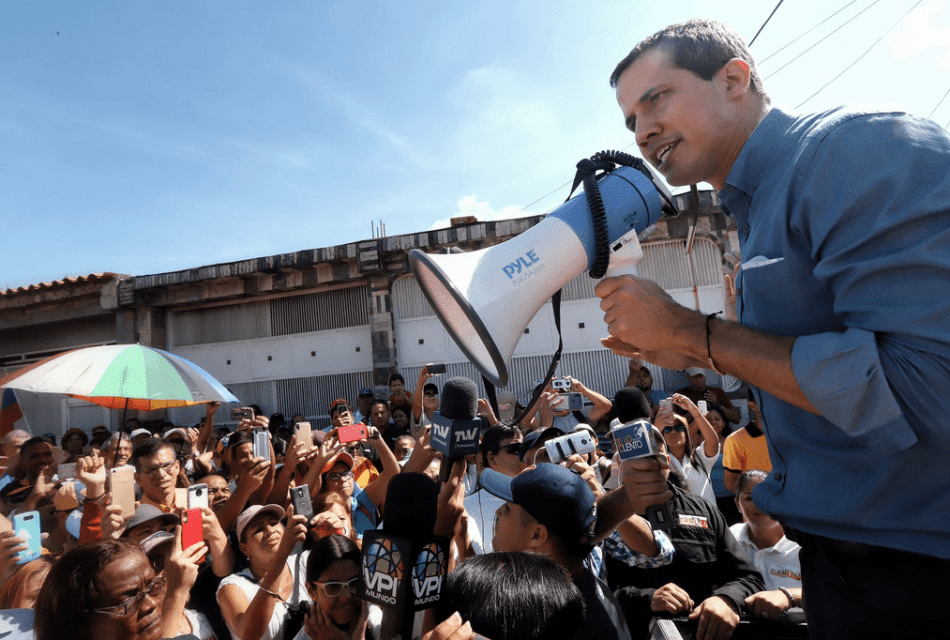

10th January 2019 marked the end of Nicolas Maduro’s presidential term, which began in 2013. Given the institutional vacuum, the Venezuelan constitution obligated the legislative branch to assume the functions of the executive branch on an interim basis. The president of the national assembly, Congressman Juan Guaido, was ultimately the interim president in charge. However, Maduro continued to occupy Miraflores, thereby usurping power.

This is how the strategy that would achieve the re-democratization of the country was proposed: “cessation of usurpation, a transitional government, and free elections” in that order. This sequence was essential because it was sure that any election under Maduro would once again produce fraud, and that a transitional government formed by the National Assembly should first reorganize the system and the National Electoral Council to guarantee clean elections. This required some time.

The plan received massive support in Venezuela and abroad from 60 democracies around the world. Remember the episode of humanitarian aid in Cucuta on 23rd February. There was widespread optimism. Those of us who were there thought that freedom and democracy would follow the trucks carrying medicines and food.

Note that this is not very different today in Bolivia. Conceptually it is identical: the parliamentary-based transitional government should call free elections under a different electoral authority, not the one that produced the 20th October fraud. And they must do so as quickly as possible. There is a talk of ninety days to resolve the political crisis and stabilize the country. Hopefully, that will be the case.

Let’s turn our attention back to Venezuela, where almost a year has gone by already. Since the formation of Guaido’s interim government, the country has never been further from the much-desired re-democratization than it is now. To the point that the same parties that proposed the sequence of the roadmap for Venezuela are now re-legitimizing Maduro’s dictatorship. In fact, Guaido’s interim presidency has moved from “the end of usurpation” to “cohabitation.”

First, the National Assembly agreed with the PSUV, Maduro’s party, to create a preliminary commission to reorganize the National Electoral Council jointly. Names of new rectors proposed for this purpose have been coming up, which would give the appearance of normalization. I say “appearance” because such elections would occur with Maduro in power.

This commission said nothing about the necessary comprehensive redesign of the electoral system, the registry, the district map, the various disqualifications, and the exclusion of Venezuelans abroad, opposition votes by definition. These are necessary conditions for the elections to have minimum credibility.

This preliminary commission rests on a second point: the return of the PSUV to the National Assembly, a decision agreed in the hermetic dialogue between Oslo and Barbados. Considering that a third of the opposition deputies do not attend sessions because they are imprisoned, persecuted, exiled, isolated, or because they lack the means to travel from their regions, the return of the Chavista bloc could produce a new parliamentary balance. The balance will be in favor of the regime, that is to say.

The third element in this new scenario is the attempt to reorganize the Supreme Court of Legitimate Justice that functions in exile. Appointed by the National Assembly in 2017, it is now the assembly itself that pressures the magistrates with a simple objective: to neutralize the court’s opinions and rulings that inconvenience Maduro’s regime and its new electoral agreement in the making. This would benefit the Supreme Court of Caracas, also a usurper, according to the constitutional norm.

In this way, Maduro could retake control of three vital institutional arenas: electoral, parliamentary, and judicial. Paradoxically, the leadership of the parliament, that is, the administration of Juan Guaido, would be the one re-legitimizing the regime. The international community, which invested resources and political energy in the end of usurpation, is already vigilant against such nonsense.

In short, both in Bolivia and in Venezuela, it is a question of defining the appropriate political sanction for whoever steals an election, that is, whoever usurps power. The history of Bolivia can be virtuous, we will know in ninety days. In Venezuela, we only know that it is improbable, if not impossible, for the end of usurpation to occur with collaboration and cohabitation.

Versión Español

Versión Español