EspañolA national strike began on Thursday in Argentina, and remained in effect until midnight. Taking place simultaneously in 40 different locations throughout the country, it interrupted distribution lines and commerce. In particular, workers demanded higher wages to compensate for rising inflation — similarly, a raise for pensioners — and solutions to the crime and insecurity throughout the country.

The general strike was initiated and led by the “Blue and White” group of the Argentina Confederation of Labor (CGT), a breakaway faction of the Congress of Argentinean Workers (CTA), and the Tramway Automotive Union, one of the unions representing subway and bus drivers.

Invoking their right to strike, these groups blocked several access points to the federal capital and other major urban centers. Affected provinces included Neuquén, Jujuy, Córdoba, Mendoza, Salta Cipolletti, and Rosario. In both the city and province of Buenos Aires, workers organized pickets in 14 areas.

However, Luis Barrionuevo of the CGT, one of the main organizers of the strike, distanced himself from those engaged in this tactic, arguing that picketing and blocking traffic have nothing to do with unemployment.

“The left has joined in on the strike organized by the CTA, the FUA [University Federation of Argentina], and the CGT. They have joined in their own way. We do not agree with the picketing; we have discussed it.”

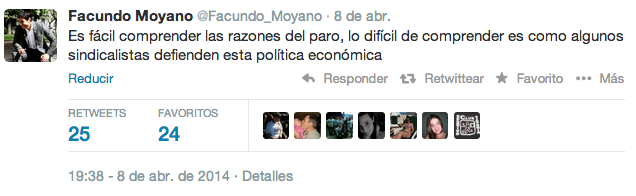

Facundo Moyano, national representative and son of the leader of CGT Hugo Moyano, stated that “the strike began because of a lack of response to concerns.” He noted, “The wage level has been declining since 2011.” Union leader Gerónimo Momo Venegas, of the Rural and Dock Workers Union (UATRE), also justified the strike by accusing the government of “fabricating bills [by printing more money] instead of allowing the production of goods,” and argued that “the state takes 75 percent of what is produced in the country in taxes.”

In a statement to Radio Mitre, Barrionuevo stated, “there is a high level of commitment to the strike.” He added that it seemed like a holiday in the capital, since bus, train, and metro operators all complied with the strike.

Cabinet Chief Jorge Capitanich said in the morning during a press conference that the organizers “aim to siege major urban centers with a large, national picket and transportation strike.”

Services that shut down included the metropolitan area unions, trains, subways (known as metros within the country), hospitals (except the emergency rooms), schools, gas stations, all domestic flights (some international), all ports, trash collection, and some banking and judicial institutions.

According to Jose Ibarra, secretary general of the Argentina Federation of Taxi Drivers, 90 percent of their members also stayed home — even though the union was not officially involved in the strike — for fear of vandalism or other repercussions.

Supermarkets remained open, along with other businesses not affected by transportation issues. Several businesses, however, were unable to open, since many of their employees were left without a way to get to work. Other companies allowed their employees to work from home, or were simply given the day off. Despite a lack of public transportation, many Argentineans opted to get to work by bicycle, carpooling, or walking.

The Underlying Problems

In response to the general strike, President Cristina Fernández Kirchner, commented that “everyone has the right to strike, and that’s fine.” However, the apparent reasons for a large part of the population to halt work in the country remain intact.

Germán Gegenschatz, a lawyer and scholar of the union problem in Argentina, believes that national strikes occur when there are fundamental problems in the economy. Speaking to the program Realpolitik of FM Identity, he commented, “When times are good, things occur peacefully and in a more organic manner. In developed economies, general strikes and violence are not present.”

For Gegenschatz, one of the principal reasons for the strike, a call to raise the incomes of retirees and pensioners to 82 percent of the minimum salary in Argentina, has occurred because there is no dialogue with the national government. There are no active communication channels with the Casa Rosada (the office of the president).

Carlos Maslatón — a lawyer, journalist, and financial analyst — supports the strike on the grounds that it has legitimate motives in the political domain.

“The real political struggle occurs when you paralyze the country,” he said during the same radio program. Maslatón identified the loss in real wages, quality of life, and the decline in purchasing power as the causes for the strike. “The adjustment variable is wages,” he concluded.

Juan Luis Espert, an Argentinean economist, also weighed in with this analysis of the situation:

“Tax evasion is around 33 percent, the tax burden on those in the legitimate market is around 50 percent of GDP, similar to the figure of many OECD countries with three to four times our per capita income. An absurd total because what the government takes from private labor through taxes should be relative to the level of income generated by these private entities, regardless of the state of public spending.”

Economic analyst Iván Carrino asserted that pressure on the state is likely to make Argentina’s economic woes worse, not better.

“If prices go up, the state — the creator of social chaos — will come to the table and ‘agree’ on some price freeze. If [general prices] go up again, the state will have no other choice than to punish the powerful speculators. For those who believe in the interventionist fairytale, this narrative is always the same. And [the interventionism] will continue this way until the inevitable path materializes: the control of all economic activity.”

According to the latest official price index, inflation increased in March by 2.31 percent, and the cumulative rise this year is now at 19.3 percent.

Versión Español

Versión Español