— As far as I’m concerned, the only sort of pro- or crypto-Nazi I can think of is yourself.

— Now listen, you queer — stop calling me a crypto-Nazi or I’ll sock you in your goddamn face, and you’ll stay plastered!

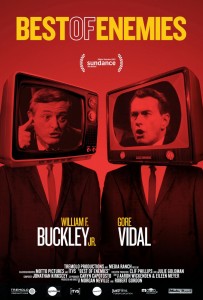

EspañolThis exchange did not take place in an uncouth, Jerry Springer-like television program. Rather, it came during ABC’s coverage of the 1968 US presidential election. Its protagonists were two of America’s most distinguished intellectuals of the 20th century: writers Gore Vidal and William F. Buckley Jr., who is considered a founder of the modern conservative movement.

It was a time of change in the United States. Color television was new. Martin Luther King had been assassinated in Memphis, and Robert Kennedy had been killed in Los Angeles. The Vietnam War raged on, and unrest consumed US society.

In the summer, while the Republican and Democratic national conventions took place, Buckley and Vidal exchanged their views in 10 debates about the deep socioeconomic, racial, and religious rifts that were sundering America apart.

But the debates were not about political ideals as much as they were about Buckley and Vidal themselves. Each represented — from the heights of society — one antipode of mainstream opinion concerning politics, culture, sex, and religion. And it only took them 30 seconds to turn the debate into something personal.

Filmmakers Robert Gordon and Morgan Neville portray the essence of the Buckley-Vidal debates in their documentary Best of Enemies. Aside from showing how the debates influenced the future of television, the film also provides insights into today’s political climate in the United States.

Both Buckley and Vidal are sharp, astute, elegant, and intelligent. They wage intellectual battle, each armed with his interpretation of current events. Since this is television, there is the inevitable indiscretion and fallacious argument.

When Buckley attacked Vidal for being the author of Myra Breckinridge, a novel with a transsexual hero, Vidal responded: “If I may say so, Bill, before you go any further, that if there were a contest for Mr. Myra Breckinridge, you would unquestionably win it. I based the entire style polemically upon you — passionate and irrelevant.”

Although such a demonstration of wit has no true parallel in today’s United States, there is a rising political figure who seems to emulate the kind of irreverence that characterized the Buckley-Vidal rivalry: Donald Trump. The garrulous Republican candidate catapults himself through the opinion polls with incendiary phrases and populist slogans, the objective of which is to question the country’s sociocultural status quo.

[adrotate group=”8″]

Other candidates regard immigration, the state of the middle class, racial tensions, religion, and the right to bear arms from a political or economic perspective. Regardless of party affiliation, political speech hovers far above ordinary citizens and their concerns. Politicians are regarded as aloof, monotone, and boring due to political correctness. Occasionally, hypersensitive students stifle any debate that disturbs the sheltered tranquility of the college campus, which is now designed to be a uterus-like safe space.

Trump, on the other hand, treats immigration, race, and religion as cultural issues. His sole objective is épater le bourgeois. Foregoing any deep analysis, while he becomes the object of his opponents’ wrath, Trump manages to get the better of his rivals time and again.

In 1968, Vidal and Buckley didn’t disappoint. Beyond their personal stance on different issues, they offered a tumultuous debate to a country in turmoil. Today, some claim that the United States is as divided as it was in the 1960s, except that the characters are different. But Trump alone has dared to launch a frontal attack on political correctness, and it has been very effective, even if his aim is hardly steady.

The debates seen in Best of Enemies also teach a lesson to Latin America, where the cultural debate still hasn’t taken place. During the past century, the region has seen coups-d’état, rampant poverty, migration exoduses, and squalid political debates based on how the government will solve people’s problems.

Latin American intellectuals never took part in a cultural battle resembling that of Buckley and Vidal. Rather, soldiers and guerrilla members fought it out across the region. In certain exceptional cases, self-styled “progressives” took up the cultural standards against a nonexistent enemy. Latin American liberals were always too conservative to take any real position. Conservatives, meanwhile, were too powerful to consider debating culture.

Chile’s descent into decadence after President Michelle Bachelet assumed power for a second time illustrates the pernicious effects of avoiding the cultural debate, in which very few are willing to take part.

When Vidal accused him of being a crypto-Nazi, Buckley tried to stand in order to fulfill his promise of “socking him in the goddamn face,” but he hesitated for an instant and returned to his august position.

Perhaps we all need a moment like that in order to identify what type of discussion we should be having.

Versión Español

Versión Español