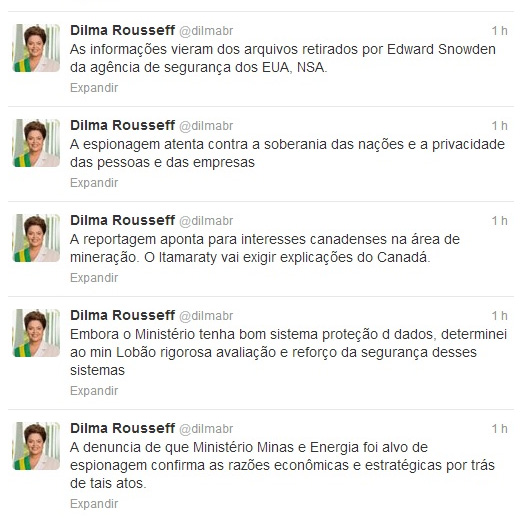

EspañolThere are two default responses to recently leaked documents that reveal Canada has been spying on Brazil’s Ministry of Mines and Energy and the state-managed oil company, Petrobras: the first, which accords with the public position of Brazilian President Dilma Rousseff, is one of moral indignation; the second, which emanates from security insiders and associated adherents of realpolitik, defends spying as “part of the game” and suggests Canada’s only mistake was “getting caught.”

Somewhere between these two positions, however, the distinction between the goals of economic competitiveness and national security appears to have been forgotten.

“Basically, everywhere and everybody that has involvement with our national security issue [is a target for economic espionage]. The concept of economic security is part of national security as well,” says Michel Juneau-Katsuya, a former senior intelligence officer with the Canadian Security Intelligence Service (CSIS) and one of the media’s go-to sources in defense of Canada’s spy network, including Communications Security Establishment Canada (CSEC), the government agency at the center of the controversy in Brazil.

“If not for the fact that terrorist acts kill people,” Juneau-Katsuya testified before the Canadian Senate Committee on Anti-Terrorism, “foreign espionage would be and should be the most pressing national security issue for Canada.”

At issue, Juneau-Katsuya says, is the fact that foreign intelligence gathering and industrial espionage — the former undertaken by national intelligence agencies; the latter, by private agents — cost Canada billions every year and put Canadian companies at a competitive disadvantage in international markets.

The problem with Juneau-Katsuya’s position, as other security and industry experts have argued (see here and here), is that the losses from economic and industrial espionage are notoriously hard to determine and are often inflated by claims of copyright or trademark infringement, which, as the former head of CSIS points out, is distinct from espionage.

Moreover, as intelligence historian Wesley Wark argues, any attempt to “level the playing field” by reverse-engineering espionage carries potentially steep downsides in the political realm, especially where select private sector companies are perceived to benefit from classified intelligence.

Glenn Greenwald, the Brazil-based journalist who is feeding Edward Snowden’s leaked US National Security Administration (NSA) documents to the media, says the first revelations about Canada’s spy program in Brazil are only the tip of the iceberg.

Unlike the NSA, which — in the face of similar espionage charges from Brazil — continues to deny sharing foreign intelligence with US companies, the Canadian government acknowledges holding classified security briefings twice yearly with key stakeholders in Canada’s energy sector.

According to Wark, Canadian government statements on intelligence activities since 2001 suggest the focus has been on “global terrorism, weapons of mass destruction proliferation, and support to military operations — things that can easily be understood as benefiting Canadian national security.”

“If the Canadian government has quietly re-engineered its intelligence priorities to include economic intelligence-gathering against friendly states, then it would be best that the Canadian public [be] made aware of this in a revamped review of national security and intelligence.”

Like Wark, Jean Daudelin, an associate professor at Carleton University’s Norman Patterson School of International Affairs, says there are “no security or economic reasons” for spying on Brazil, which accounts for less than one percent of Canadian imports and exports.

From Brazil’s perspective, however, things may look a little different.

In 2007, Brazil announced that it had found the largest known oil reserve outside of the OPEC bloc. Brazil put its Ministry of Mines and Energy in charge of auctioning off rights to help Petrobras exploit the reserve. The auction, in September of this year — roughly one month after leaked documents showed the United States was spying on Brazil, and one month before Canada was caught in a similar act — was expected to attract as many as 40 bidders. Instead, it drew only 11, and not one from the territories of the so-called “Five Eyes” intelligence network that includes the United States, Canada, United Kingdom, Australia, and New Zealand.

As the CBC’s James Fitz-Morris says, “we are left wondering why not one energy company based in the [“Five Eyes” network — Exxon, Chevron, and BP, for example] is participating in an auction for what is billed as the largest oil find in 40 years. And how they got the information on which they based their decision.”

Juneau-Katsuya and others who defend Canada’s spy network are undoubtedly correct to point out that the Brazilian president’s much publicized demand for the Canadian government to explain its involvement in spying on Brazil is, at least in part, an exercise in political theater. A recent poll suggests approval ratings for Latin American politicians are positively correlated with anti-North American sabre rattling. After months of often violent anti-government protests in Brazil, Rousseff could use a rhetorical reprieve.

But this does not absolve the Canadian government of answering critics who question why Canada was targeting Brazil in the first place.

While reactionary adherents of realpolitik seek to discredit as naive any attempt to question Canada’s involvement in the Brazilian controversy (see here, here, and here), nothing is arguably more naive than giving government a blank cheque for national security. Once we recognize that resources for national security are limited, then questions about where Canada is focusing its intelligence efforts, and why, are paramount.

It is entirely possible, Wark reminds us, that the Brazil operation “was not really a made-in-Canada operation, but rather a task undertaken by Canada as part of its alliance objectives within the very secret world of the so-called ‘Five Eyes’ system.”

If this is the case, then Brazil and other Latin American countries may be forgiven (again) for doubting Canada’s commitment to a hemispheric engagement policy. This commitment, affirmed by Prime Minister Stephen Harper in 2007, is supposed to demonstrate the distinctiveness of Canadian leadership and open a new chapter in north-south relations that positions Canada as an independent and largely sympathetic regional ally.

Targeting global terrorist cells and tracking the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction is one thing; and few would likely reject outright the claim that national security includes understanding how terrorism is financed. Without a doubt, Canada must monitor the potential security threats that exist in Latin America (most notably in the ALBA bloc, including Brazil, where Hezbollah is known to operate).

But this does not mean that the national security doctrine should be automatically and uncritically accepted as a pretext for making unsubstantiated or exaggerated claims in favor of economic nationalism. To argue that a “loss of competitiveness” in select industries (Juneau-Katsuya’s justification for economic espionage) is tantamount to a wholesale assault on economic security invites mission creep in the national security doctrine, the application of which becomes highly discretionary and open to corruption.

As one critic of US spying on Brazil observes, if the NSA is concerned about threats to economic security it should have focused more time on Lehman Brothers and Bear Stearns and less time on Petrobras.

Likewise, given that Canada’s largest trading partner has taken to holding markets hostage as it flirts with insolvency, the Canadian security establishment might do well to ensure that at least one of the “Five Eyes” is firmly fixed on Washington.

Versión Español

Versión Español