EspañolHeavily armed “mega-gangs” have taken over poor neighborhoods in Venezuela, according to the director of the Organized Crime Observatory, Luis Cedeño.

The sociologist says there are at least 10 mega-gangs currently operating in Venezuela, a product of prison culture transferred from jails to poor neighborhoods. Two organizations have become especially popular, and have had numerous confrontations with authorities: El Picure and El Juvenal.

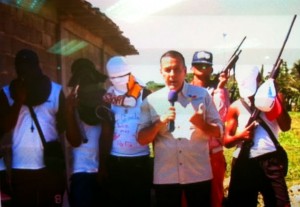

Cedeño explains that “mega-gangs” are defined by the number men in the group and the firepower they possess. Each mega-gang is comprised of at least 60 members, and are known to carry AK-47 and AR-15 rifles, as well as explosives.

He says the government’s failure to curb criminal-gang activity reached its peak with the creation of “peace zones,” territories that are off-limits to police, where gang leaders are left to impose their will unabated.

“The Venezuelan government has been permissive in regards to crime. This stems from the justice system’s role in creating impunity, as well as from the concoction of the so-called ‘peace zones,'” Cedeño says. “The supposed intention was to diminish homicide rates by avoiding confrontations among gangs. But it backfired, causing other types of crime to increase in these areas that are now run by criminals.”

The expert referenced events of Monday, July 13, when the military and police deployed over 3,000 agents to combat illegal activity in four areas of the country where large gangs operate. The government called it “Operation for National Liberation and Protection (OLPP),” according to Interior and Justice Minister Gustavo González.

During the operation, authorities apprehended 247 people, recovered 28 stolen cars, and killed 17 gang members. According to authorities, among those detained were 40 Colombians allegedly linked to paramilitary groups.

“We’ll see if the government really intends to liberate all the areas that have been overtaken — not just by the gangs but also by armed colectivos — using the prison model which revolves around a leader that imposes his own rules, has a large number of followers, and makes crime a way of life,” Cedeño said.

For lawyer and criminologist Fermín Mármol García, the rise of these mega-gangs dates back to 2012, when the National Pacification Plan was established during the Hugo Chávez administration. The government’s plan was to have criminals give up their life of crime in exchange for work in the agriculture industry.

“That type of proposal simply does not make sense in Venezuela, since the criminal knows full well he will make more money in crime than by working in a field. This led to gangs becoming stronger, larger, and taking over entire areas of the country,” Mármol García explained.

Camouflaging Crime

According to both experts, the increase in crime in poor neighborhoods, coupled with the government’s neglect, has forced residents to adapt.

“Venezuelans have no choice but to get used to living surrounded by crime and violence, because the state has abandoned them and their duty to protect them, pursue criminals, and suppress crime. People have so many problems, that they don’t have any choice but to adapt to survive,” Mármol García said.

Cedeño says it is precisely this fear that has turned communities passive in the face of the rise of these criminal mega-gangs, which ultimately replace the state in these areas as the law of the land.

“People know there is no rule of law, and that whoever substitutes it is welcome,” he says. “In the end, it is the lesser of two evils when compared to absolute defenselessness. People prefer to get used to living with an organized mega-gang, than to have several gangs spread out confronting each other.”

Versión Español

Versión Español