EspañolThe current Venezuelan National Assembly will hastily assign 21 new Supreme Court magistrates today even though these appointments should be made by the new, opposition-led congress, which will be sworn in on January 4, 2016,

National Assembly members were summoned to four extraordinary sessions on December 22 and 23 for this purpose; usually, Congress ends its last session of the year on December 15, but the current ruling party majority decided to delay its recess after the opposition’s recent victory in the parliamentary elections.

On December 22, the Supreme Court’s Constitutional Chamber issued a ruling stating that all extraordinary sessions in the National Assembly have legal validity. This means that any decision that outgoing congressmen approve will be legitimate.

By appointing 21 new Supreme Court magistrates, Chavista congressmen would be able to avoid investigations against members of congress and government officials being prosecuted in foreign courts. The measure also hinders the discharge or impeachment of the president, ministers, members of the armed forces and other high-ranking functionaries.

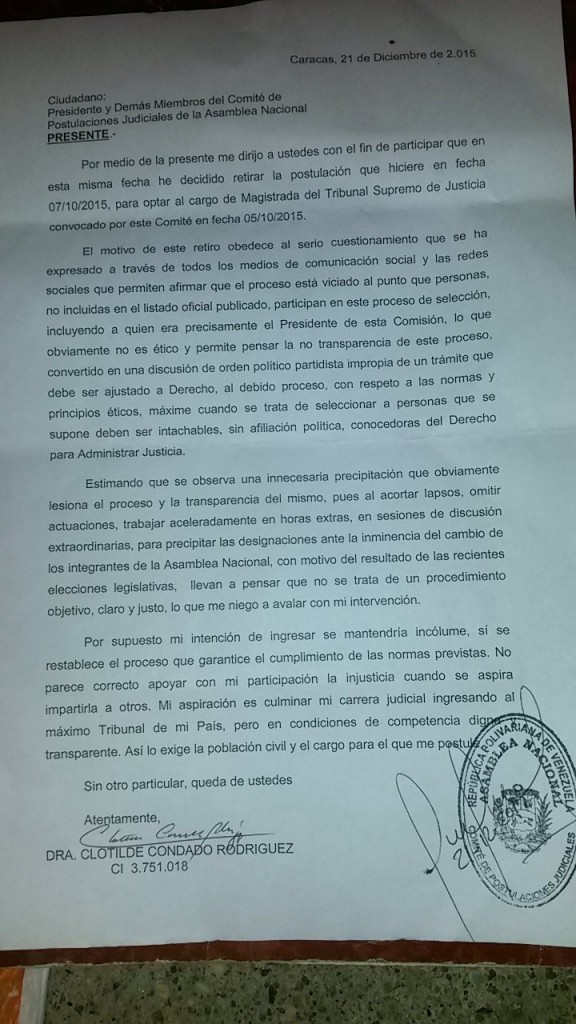

Blanca Rosa Mármol de León, a retired Supreme Court judge told the PanAm Post that a group of emeritus magistrates and practicing lawyers contested the nomination of over 300 candidates since they didn’t meet the selection criteria.

Mármol de León stated that the National Assembly must follow due process and demand that all candidates prove that they are qualified to occupy the offices to which they aspire. She adds that congressmen insist on making the appointments despite the contestation.

The names of the 21 chosen magistrates were announced on Tuesday, with spokesmen assuring that “each of them fulfills the Venezuelan state’s requirements.”

A Hasty, Unconstitutional Measure

José Vicente Haro, a law professor at the Central University of Venezuela (UCV) who heads the Venezuelan Association of Constitutional Law, explains that this forced designation violates the country’s constitution. The National Assembly is overstepping its boundaries by making these appointments, he tells the PanAm Post.

“The National Assembly is rushing to make these unconstitutional appointments in order to obtain a pro-government majority in the judicial branch so that the Constitutional Chamber can block parliamentary initiatives once the opposition takes over,” he says.

Haro also agrees with Mármol de León in that the majority of the candidates don’t meet the criteria required for Supreme Court magistrates.

He explains that, according to the constitution, a new Supreme Court magistrate must have at least 15 years of experience as an assigned judge, as a law professor, or as an accredited attorney

He adds that the new magistrates are being named by means of a “fraudulent retirement” imposed on current magistrates, whose term ends in 2016.

This was approved three days after the December 6 parliamentary elections.

The New National Assembly Is Being Cornered

Haro says, however, that the new National Assembly will count with the legal tools to revert the appointments. The problem is, he explains, that opposition congressmen will need the support of government officials — among them the Attorney General — who are government supporters.

New National Assembly members could declare the appointments null and void. The Supreme Court’s Constitutional Chamber, however, could overturn the decision.

According to Haro, the opposition would then be left with the option of introducing a constitutional reform or summoning a national constituent assembly so that voters can decide on the issue via a referendum.

[adrotate group=”8″]

Desperate Post-Electoral Measures

After its electoral defeat on December 6, the ruling party has taken other measures in haste in order to safeguard its political power. In the first place, Susana Barreiros, the judge who sentenced opposition leader Leopoldo López, was named General Public Defender. Several international human rights organizations have criticized Barreiros for her decision in the López case.

The National Assembly approved a legal reform to grant Barreiros immunity from removal from her post, which can only be authorized by the Supreme Court or the National Council on Morals.

Lastly, the government has tried to speed up the creation of the Communal Parliament and to give it functions parallel to those of the National Assembly. The Communal Parliament forms no part of the constitution and seeks to legitimize non-elected lawmakers. Haro argues that this body has “no legal authority.”

Versión Español

Versión Español