EspañolIt always follows the same pattern: “foreign” capital buys a Venezuelan media outlet; it’s never (or almost never) known who the new owners truly are, but usually consist of firms with flamboyant names that operate via financial trusts in Vermont, or an empty office in Madrid.

Next up is the petition for “neutrality.” The newspaper or TV channel, it’s argued, favors the opposition. It needs to offer more airtime to the government line. What follows are petitions to “turn down” the volume of anti-government complaints.

Finally, uncomfortable journalists who refuse to toe the new line or drop embarrassing investigations are fired, or placed in irrelevant positions from which they’re forced to resign.

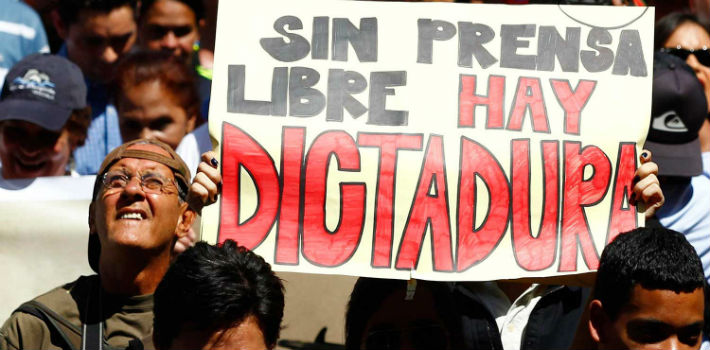

Those who remain are forbidden to interpret, analyze, or prove context to the news: plain, flat journalism is the order of the day. Thus Venezuelan society ends up hearing only one voice: that which comes from on high, from the government of President Nicolás Maduro.

These are some of the findings of the “Owners of Censorship” investigation carried out by the Press and Society Institute (IPYS), a Venezuelan NGO that since 2013 has been researching the purchase of 25 media outlets during the past five years.

The report, presented in seven videos on Thursday, March 5, documents the cases of Grupo Últimas Noticias (formerly Cadena Capriles), El Universal, and affiliated regional papers Versión Final, El Norte, and Nueva Prensa de Guayana.

The IPYS also tracked the sale of TV channel Globovisión and several provincial radio stations, including the effective confiscation of Circuito Nacional Belfort (CNB), one of Venezuela’s largest radio broadcasters whose frequencies were handed over to broadcasts from the National Assembly. Finally, the institute examined a group of media outlets openly controlled by the Social Fund of state petroleum firm PDVSA, in areas where the company holds exploration fields and refining operations.

The video details growing pressure on independent media companies. Globovisión faced 13 legal proceedings filed against it by the National Telecommunications Commission in 2012-2013, only to see these sanctions dropped without comment when the channel was bought by business figures linked to the government.

Despite formerly being “bête noire of the revolutionary regime,” the channel turned down the heat on Maduro’s government rapidly after being acquired by businessmen Raúl Gorrín, Gustavo Perdomo, and Juan Cordero. Journalist Diana Ruíz told the IPYS how she was fired for making a simple mention of scarcity: a word, along with inflation, that’s now been expunged from the channel’s vocabulary.

News anchors are further barred from reporting homicide statistics, and can only present isolated murder cases. A list of individuals are prohibited from being mentioned or invited on the channel, and reporters must contend with their stories being modified after publication, disappearing from web pages on a daily basis, or never being published at all.

The breaking point for many Globovisión journalists proved to be on February 12, 2014. While violent clashes between protesters and state-security forces near the Attorney General’s Office in Caracas (for which authorities arrested opposition leader Leopoldo López a week later, and remains imprisoned) were ongoing, the news channel transmitted archive programs. Aside from López, five members of the Bolivarian Intelligence Service (SEBIN) are accused of the murder of a young protester, Bassil Da Costa, near to the disturbances.

The same incident marked a turning point for Grupo Últimas Noticias. A striking audiovisual report about the events of February 12 from its investigative department won an IPYS prize and helped lead to the presentation of the judicial charges against the SEBIN officers.

Tamoa Calzadilla, a well-respected Venezuelan journalist, reported that a short time later her boss Eleazar Díaz, who had remained in place since before the sale of the company, demanded that she produce a report “condemning the guarimbas (barricades erected by student protesters) and claim they were ‘financed from abroad.'” Such an interpretation mirrors that maintained by the Maduro government. Calzadilla resigned her post.

In the chain’s economic daily El Mundo, Director Omar Lugo was fired over a headline referring to inflation. Even the group’s sports daily, Líder, has faced editorial pressure from the government.

In the case of El Universal, staffers reportedly resent the new line the newspaper is taking, above all in the Economy section. Its Versión Final, El Norte, and Nueva Prensa de Guayana titles have all faced lawsuits, internal complaints among its shareholders, or moves by the regional authorities to restrict editorial freedom.

In the case of radio broadcasting, the IPYS report signals that large national blocs of coverage have been dismembered due to government pressure. “There remains a kind of patchwork of islands; in the provinces, where radio predominates as a means of information, broadcasters have become means of entertainment,” IPYS spokesman Ciro Ramones said.

“Opinion programs are few … there’s self-censorship, changes made to other content to keep it on air … but the pressure isn’t only for opposition sectors,” the IPYS investigator noted. “Here in Maturín [Monagas State] it also reaches … dissident voices within the government itself.”

The report came in a week when the president accused Televen, one of the few television channels considered to be relatively independent, as being behind an alleged coup d’etat, and described journalists with the Efe news agency as “stupid” for suggesting that a “leftist military coup” could take place in Venezuela. IPYS Director Marianela Balbi indicated that the study was carried out by more than 30 journalists with the collaboration of webpages Armando.info and Poderopedia.com.

Balbi suggested that the issue of media ownership in Venezuela is “crucial for freedom of expression.” The report, however, was not covered by any of the national media outlets, including any of those mentioned in it.

“Consumers have the right to know who are the owners of the media that they’re reading or viewing,” she concluded. “This investigation reveals the links between these media outlets and the powerful figures that are behind them.”

Versión Español

Versión Español