EspañolFor nearly 7,500 days, Argentina has suffered from an open wound, a debilitating uncertainty about the truth of what happened on July 18, 1994. Eighty five people died that day in a terrorist blast directed against the Argentinean Israelite Mutual Association (AMIA), the country’s principal Jewish community center.

Three days later, tens of thousands of people gathered outside the National Congress, with one demand: justice.

Alberto Nisman’s death only heightens the sense of state betrayal, which few doubt bears responsibility and complicity in the AMIA case.

The demonstration on July 21 became known as “the march of the umbrellas.” It was a rainy day in Buenos Aires, and umbrellas filled the streets. After 20 years and six months, the umbrellas stay open and the demand for the truth remains the same. During the act of commemoration for the bombing’s victims every July 18, their families and friends can’t simply remember them in peace, but doggedly raise their voices to call for justice once more.

Yet year after year, the hope that those responsible for such a criminal act will receive their just punishment is vanishing. Now, the death in uncertain circumstances of Alberto Nisman, the prosecutor in charge of the investigation, only heightens the sense of state betrayal, which few doubt bears responsibility and complicity in the AMIA case.

From the very beginning, the AMIA bombing was destined to cement government impunity. Already in the initial stages of the investigation, the highest levels of political power put the Argentinean judiciary at the service of injustice.

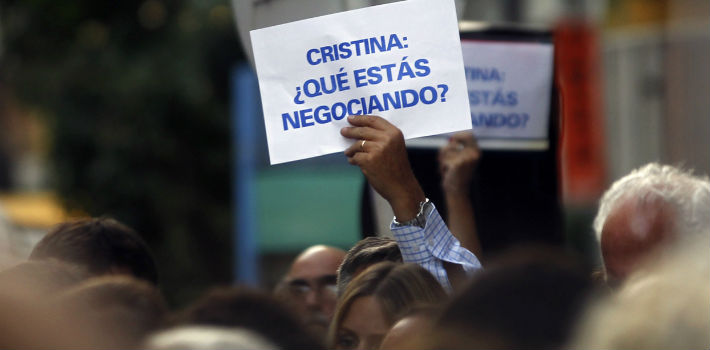

From the former President Carlos Menem, accused of forcing former investigating judge Juan José Galeano — since fired for several irregularities — to abandon one of the lines in the investigation, to the current President Cristina Kirchner, all have been complicit in a cover-up of colossal proportions. Along the way, police officers, intelligence agents, judges, prosecutors, ministers, and senior and middle-ranking officials have all done their part to prevent the truth from coming to light.

Argentina has long been a country where those who should investigate do the covering up, those who should protect and guard look the other way, and those who should place a limit on power act without restrictions. Every state body connected with security and justice is implicated in the attack, in one way or another. Each has lent their back to constructing a poisonous, superficial falsehood about the murder of 85 innocent individuals.

Hopes of reaching the truth have died once more. A husband and a father also lies dead. The death toll rises to 86.

Since he assumed responsibility for the case in 2004, Nisman began to challenge unflinchingly the hypothesis that came out of Tehran. In 2006, in a report that ran to over 800 pages, the prosecutor described how high-level Iranian officials, including former President Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani, had planned the attack, and how operatives belonging to Lebanese terrorist organization Hezbollah carried it out.

The investigation seemed to be proceeding like never before. After Nisman threw down the gauntlet, Interpol issued orders for the arrest of several of those accused. Would this be the moment where the screen of impunity around the terrorist attack was finally brought crashing down? It goes without saying that these hopes were soon dashed.

In 2011, the late journalist Pepe Eliaschev anticipated the allegations that Nisman leveled on Tuesday, January 13, past against President Kirchner. “Argentina’s no longer interested in resolving the attacks, but rather prefers to improve its economic relations with Iran,” stated a report by the Iranian foreign minister on the Argentinean position, according to Eliaschev.

Two years later, Kirchner announced the signing of a memorandum of understanding with her Iranian counterparts that transformed the judicial case into a purely political issue. The Iranians now played a different role: they were no longer on trial, but became collaborators in clearing their own name and helping the “truth” emerge about the fateful July day in 1994.

The death of Nisman is yet another confirmation of the state impunity written into the very genes of the AMIA case. Hopes of reaching the truth have died once more. A husband and a father also lies dead. The death toll rises to 86.

Buenos Aires today, on January 19, threatens rain, just as it did on July 21, 1994. Today, once again, the scriptural injunction echoes down the ages to those of us that still live to call for the truth: “Justice, and only Justice, you shall pursue.”

Versión Español

Versión Español