Spanish – According to a commission of Venezuelas the National Assembly, $11.0 billion belonging to state-owned Petroleos de Venezuela, PDVSA, vanished due to various corruption schemes between 2004 and 2014.

Few can escape. The money was deposited in too many accounts.

The big white party

“This party was born to make history,” Romulo Betancourt said in front of a crowd at the Plaza del Nuevo Circo in Caracas on 13th September, 1941. That day was the announcement of the formation of the country’s first great modern political force. It was the beginning of an era. “The party is born, armed with a program that is in tune to the needs of the people, of the nation (…) Democratic Action aspires to be the cement what unites all Venezuelans who love their nationality.”

And he did it. Modern Venezuela is nothing but a sculpture chiseled by Betancourt’s heirs. It was carefully sculpted by the party that was in power for more than five terms over four decades. Moreover, they never truly lost control when they weren’t the ruling party.

The last republican stage of Venezuela is the history of Democratic Action and COPEI. We can attribute those achievements and triumphs that made Venezuela an idyllic society to the men, who, despite their inexperience, devised the country’s present. It is true, so are the errors. Their vices eventually led to the rise of a former coup leader and lieutenant colonel (Hugo Chavez). However, it doesn’t matter; we can’t reflect sensibly on those decades without acknowledging the historical greatness of Democratic Action. The party made history.

Today, a true “Adeco” will speak nostalgically about the “party of the people.” After the last great work of an ambitious new cadre, the rebellion against their own party that led to the dismissal of Carlos Andres Perez, and the decline has been rapid thereon. Unstoppable. And although every one believed that only corpses remained of the “Adecos” and “Copeyanos”who once dominated Venezuelan politics, the media boom surrounding Henry Ramos Allup when he assumed the role of the party General Secretary in 2003 did not automatically produce the restoration of the Democratic Action to its former glory.

Today, the grand party founded by Romulo Betancourt is not even the shadow of the old ambitious project from the mid-twentieth-century. From a historical political force, Democratic Action became a machine purportedly opposed to Chavismo, while maintaining economic and political ties with the regime it supposedly opposes. It has an entire network of connections, some more distant than others while plundering money from the once most prosperous country in the continent.

The contributor

Gerardo Hernandez met Henry Ramos Allup in the mid-2000s. Hugo Chavez had already emerged victorious, purportedly, from the recall referendum against him in 2004. However, Hernandez, along with his organization, and Ramos Allup, insisted that there was a fraud.

Hernandez, who had been invited by a young and stellar white party militant, Vanessa Friedman, sat in the office of the secretary-general of Democratic Action. They discussed the strategy they would follow in the face of the election fraud committed by Hugo Chavez in the 2004 referendum. “We were in tune. Ramos Allup understood that Chavez has committed fraud and was willing to denounce it,” said Hernandez.

However, beyond the apparent lucidity of the secretary-general of Democratic Action, something caught Hernandez’s attention. Friedman was not just a romantic and attractive activist. The young woman was also a party contributor. She was sitting there with her boss, spoiled with special affection for being one of the Democratic Action financiers.

“She commented on it several times during the meeting. She boasted of financially supporting Ramos Allup’s party. Moreover, he didn’t say anything,” says Hernandez, who also points out, “At that moment, I felt that Ramos Allup understood well what was happening with Chavez. I insist we were in tune. But then something changed.”

The Ramos and the Morillo

Friedman was an emerging star of the party with her voracious energy, vigor, and clear commitment to oppose Chavismo. She stood out, of course, but also became one of the favorites of the party secretary-general, Ramos Allup, who acutely noted her talent early on.

The young woman had a relationship with another energetic young man, Francisco Morillo. “They were the typical eastern Caracas couple. Both very good-looking, from a good family,” says one of Friedman’s close friends. They knew each other since they were thirteen, and by the time Guillermo Hernandez meets Henry Ramos Allup in his office in the Romulo Betancourt Building in Caracas, the two were already married.

Morillo had been the business heir to Wilmer Ruperti, a renowned maritime businessman who had made a significant fortune through contracts with the Venezuelan state. Ruperti’s position at the end of 2002, against the oil strike that sought to destabilize Hugo Chavez’s regime, won him considerable support from Chavismo, helping him to position himself very well in the Bolivian business elite.

However, Ruperti’s criminal environment made Morillo uncomfortable. He argued so when he broke off ties with his financial sponsor. Morillo, after he separated from Ruperti, worked at the state oil company for several months and, due to political interests, ended up venturing into the oil world by setting up the consulting firm Waltrop Consultant together with former PDVSA employee Leonardo Baquero.

Thanks to his networking while working with Ruperti, and Baquero’s connections, Waltrop Consultant had access to several businesses that receive spot contracts and PDVSA tenders. Waltrop Consultant began to advise these companies.

So far, everything seemed legitimate. “When Morillo broke up with Ruperti, he was only looking to get away from Chavismo, or at least that is what he was saying,” said Friedman’s acquaintance who chose to be anonymous. Vanessa Friedman did not suspect anything. She trusted the man she knew since her childhood. She enjoyed, of course, the full flow of money from the prospering new consultancy.

After Waltrop, as we are all too greedy, Helsinge Inc was founded in Panama in 2004, “a company specialized in the physical trade of energy products and petrochemicals,” according to its website. Baquero and Morillo managed to open branches of the new company in Miami, Geneva, and Jersey, a British island. Their objective behind founding Helsinge Inc. was to avoid the limitations of a consulting firm and have first-hand access to the bids and spot contracts issued by PDVSA.

Morillo’s economic rise was noticed by those who knew him and was immediately appreciated by Democratic Action. Friedman, his wife, received all the affection of those who, in fact, are quite reserved. Henry Ramos Allup and his wife, Diana D’Agostino, became his political protectors. And both families took a liking to each other.

**

A source, who was a member of the National Executive Committee (CEN) of Democratic Action during those years, confirmed to the PanAm Post under the condition of anonymity that the Morillo-Friedman family contributed large sums of money to the party. “Sums of five thousand USD, also of 10 and 15 thousand USD. Moreover, Henry Ramous has an excellent relation with Francisco and Vanessa,” said the former member of the CEN.

Guillermo Hernandez, who later maintained contact with Friedman, corroborated the amounts of the former Democratic Action activist.

“I remember that meeting clearly, and then they told me that they had collaborated with the party,” insists Hernandez. However, when he sat in that office with Ramos Allup and the young Friedman, the conflict had not yet begun. It was a few years away.

The relationship between the secretary-general of Democratic Action and the couple from Caracas continued to solidify until 2007 when the D’Agostino family considered it was time for Henry Ramos Allup’s children to start working in the oil world. The middle one, Ricardo Ramos D’Agostino, started working in Helsinge thanks to the mediation of Vanessa Friedman, who was fond of Ramos’ heirs.

Friedman’s illusion of prosperity started breaking when she discovered that a massive web of corruption and relations with the Hugo Chavez regime were behind her husband’s wealth. The revelation was a result of several clumsy gaffes and created a crack in their relationship, which eventually led to their divorce.

That decision, though personal and perfectly rational, led to the breakdown of another illusion: the fantastic relationship between Henry Ramos Allup, his party, and Vanessa Friedman. The result was ostracism. Also, a whole process of harassment and hounding was triggered after Friedman suggested that Henry Ramos Allup’s children leave her husband’s company because of the possibility of being tarnished in a scandal that would eventually explode.

Ricardo Ramos D’Agostino did not leave Helsinge Inc, and the party expelled Vanessa Friedman. In fact, three sources who worked in the Adeca mayor’s office of Myriam Do Nascimento in El Hatillo confirmed to the PanAm Post that Henry Ramos Allup gave the order to expel Friedman from the town hall where he worked.

“Vanessa, by messing with her husband and wanting a divorce, also messed with Henry Ramos Allup and his business with Morillo,” commented a source who worked in the mayor’s office of Myriam Do Nascimento at the time.

The scandal explodes

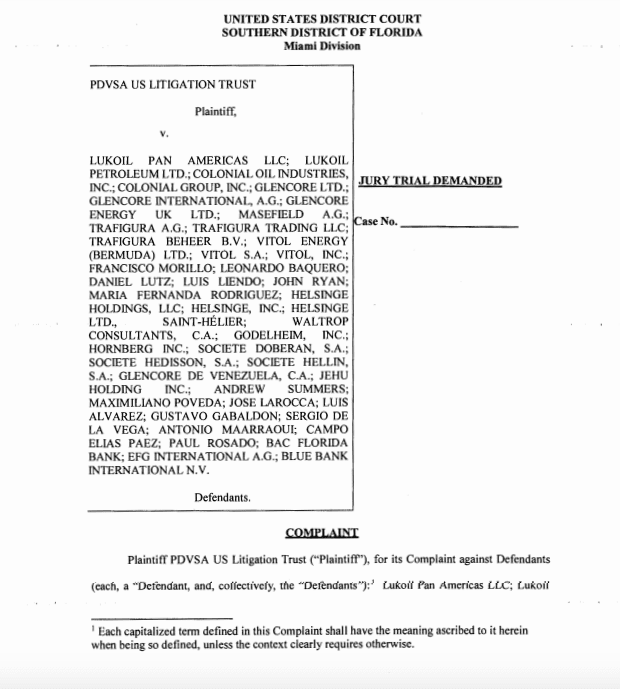

In March 2018, Reuters reported the lawsuit of a trust called PDVSA US Litigation Trust against a group of companies for weaving a web of corruption and fraud against the Venezuelan state-owned oil company. Although the lawsuit could be driven by an attempt for revenge, according to journalist Alek Boyd, who has been one of those who have followed this plot closely, the move uncovered what could be one of the biggest corruption scandals committed during the Chavista embezzlement of Venezuela. A small company appears in the center of the accusations: Helsinge Inc.

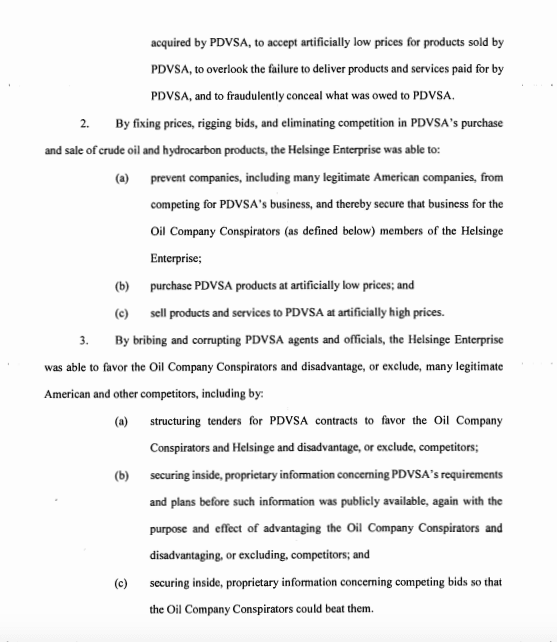

According to the lawsuit, which the PanAm Post could access, the “action arises out of an ongoing conspiracy (Helsinge Inc.) between international oil companies and traders, their banks and conspirators, including corrupt agents and an official of the Venezuelan state-owned company Petroleos de Venezuela, S.A..” (PDVSA): a) to fix prices, rig offers, and eliminate competition in the purchase and sale of PDVSA crude oil and hydrocarbon products; b) to embezzle PDVSA’s data and intellectual property; c) to systematically loot PDVSA by making corrupt officials pay inflated prices for products and services.

Specifically, according to the “natural actions” of the lawsuit, Helsinge Inc was able to weave a web of corruption by bribing PDVSA officials. Also, thanks to the help of a hacker, Luis Liendo, the company of Francisco Morillo and Leonardo Baquero was able to clone the PDVSA server and, in this way access privileged information that it later sold to different oil companies around the world. “This procedure would give real-time access to contractors and their clients, who would know the bidding information before other competitors,” wrote Venezuelan journalist Maibort Petit.

The lawsuit reads as follows: “As the conspiracy progressed, Helsinge Inc was able to gain direct access to PDVSA’s proposed servers (…) all of this enabled Helsinge Inc to misappropriate PDVSA’s sensitive information (…) PDVSA’s losses and profits for defendants, as a result of crimes committed by Helsinge Inc, amount to many billions of dollars.

All the information for the lawsuit was provided by the researcher John Brennan, founder of the American company The Brennan Group LLC, who became a “senior detective” of the renowned British police Scotland Yard. His investigation had the contribution of Vanessa Friedman, who managed to save thousands of documents that directly accused her ex-husband, Francisco Morillo.

In a statement for the lawsuit, renowned detective Brennan says: “My investigations have revealed that two Venezuelans, Francisco Morillo, and Leonardo Baquero, and several conspirators, have bribed PDVSA employees to obtain direct electronic access to PDVSA’s highly confidential internal information. These conspirators have used this access to defraud PDVSA and manipulate the market.”

Brennan says in the lawsuit that he interviewed “numerous individuals in the United States, Venezuela, and other countries.” He also reviewed several documents and emails.

One name stands out among those bribed by Morillo’s company and Leonardo Baquero: Rene Hecker, who, according to Brennan, “met both when they worked at PDVSA.” “We understand from our informants that Hecker held the position of commercial manager of PDVSA’s Commerce Department until 2013,” says the British researcher.

Rene, as confirmed to PanAm Post by a source close to the case, is the brother of Ricardo Hecker. He is also close to Morillo and “legal consultant” to Chavista Major General Miguel Rodriguez Torres, who at the time was the head of the Hugo Chavez government’s intelligence. In fact, it would be thanks to the contact with Rodriguez Torres (that is, the intelligence of the regime) that Helsinge Inc would obtain access to such privileged information from PDVSA and could hack into the state-owned oil company.

“Rene Hecker continues to be one of Morillo’s principal contacts within the PDVSA, in his current role as head of Petropiar S.A., the joint venture between PDVSA and Chevron,” says John Brennan.

According to the lawsuit and information published by investigative journalists Alek Boyd and Maibort Petit, some of the companies that benefited from the information Helsinge Inc was illegally accessing were Russian oil company Lukoil, Swiss multinational Glencore, and Singapore-based multinational Trafigura.

Brennan reports that these companies are among “PDVSA’s biggest buyers of crude oil and sellers of light crude oil for PDVSA. “Their transactions with PDVSA over the past 15 years have totaled tens of billions of dollars,” he says.

According to the British citizen’s testimony, based on thousands of documents to which he gained access, Helsinge Inc charged companies that participated in the “conspiracy” between 15,000 USD and 150,000 USD monthly. Furthermore, it added a profit percentage of 0.22 USD for each barrel of oil or product traded.

All of this information was corroborated by John Thackray, an American forensic scientist and vice president of GetData USA, who in 2010 was recognized by the Criminal Division of the U.S. Department of Justice “for outstanding performance in computer training and clinical forensic analysis.”

The descendant of the white party

On March 12, 2018, four days after the lawsuit against the group of companies became public, Associated Press journalist Joshua Goodman reported the arrest of two executives of Helsinge Inc in Switzerland.

“The executives were arrested in the last few days after accusations were included in a complaint against PDVSA (…) The Geneva prosecutor’s office confirmed the arrest of Helsinge Inc executives on suspicion of corruption and money laundering,” A.P. reported.

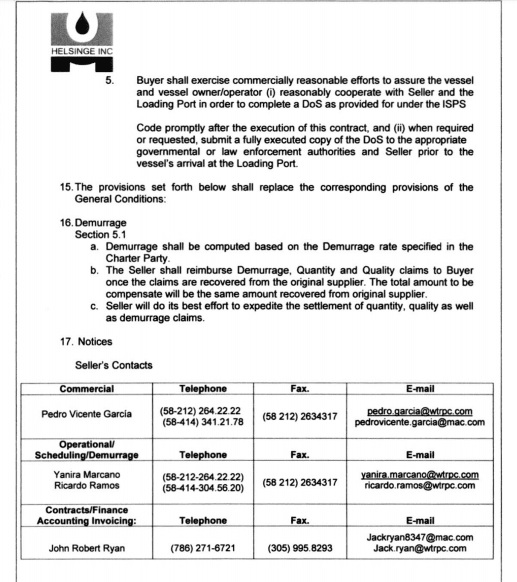

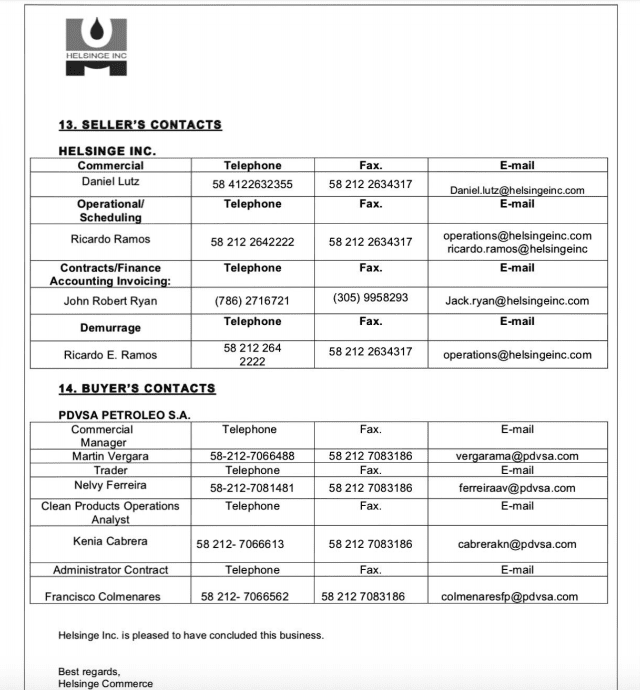

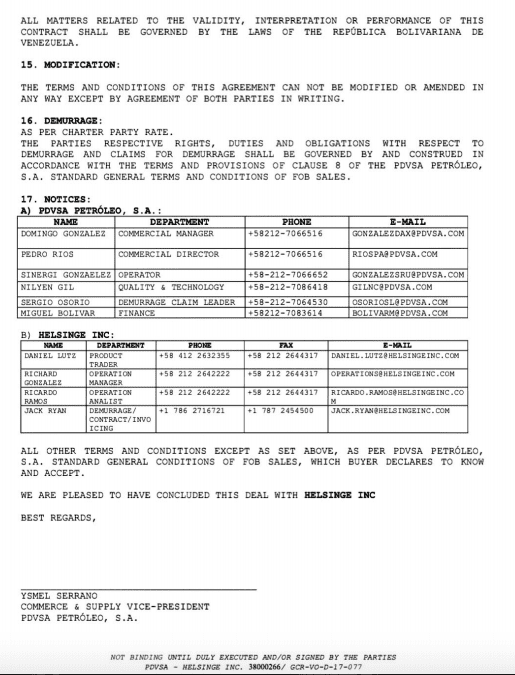

One of the detainees, John Robert Ryan, appears in various documents as one of the contacts of Helsinge Inc. Another name that appears among the contacts is Ricardo Ramos D’Agostino, son of Henry Ramos Allup and Diana D’Agostino.

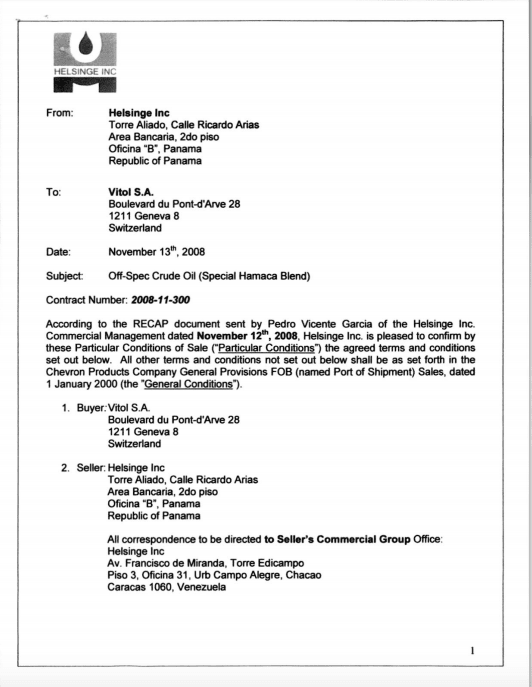

The oldest document to which PanAm Post had access is from 2008. It is a commercial exchange between Helsinge Inc and the Swiss oil company Vitol. The buyer’s contact numbers -in this case, Helsinge Inc- include Pedro Vicente Garcia, John Robert Ryan, and Ricardo Ramos.

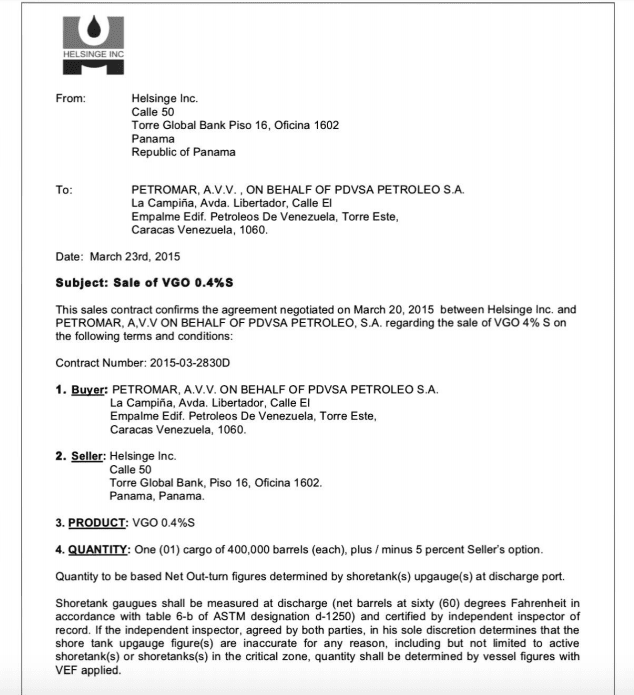

Another, more recent document dates from 2015, some nine months before Henry Ramos Allup became president of the National Assembly. In this case, a sale of vacuum gas oil to Petromar, “in the name of PDVSA,” also appears the name of Ricardo Ramos among the contacts of Helsinge Inc.

During the presidency in the parliament of the secretary-general of Democratic Action, white party activist Luis Aquiles Moreno was appointed the chairman of the Assembly’s Energy and Petroleum Commission. Two party-members told PanAm Post that during those months Francisco Morillo was regularly visiting Moreno’s office. Another activist, who was a member of the National Executive Committee, claims that Morillo went so far as to advise the Energy and Petroleum Commission. This could not be confirmed.

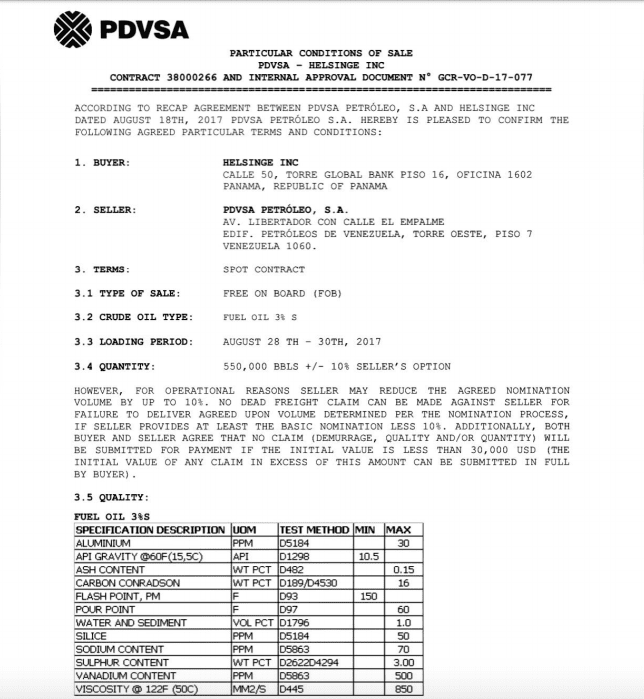

Finally, surely the most revealing document is from August 30, 2017, when Ramos Allup had already left the directive of the Venezuelan Parliament. The report is an archive of PDVSA and is the sale of a “spot contract” for 550,000 barrels of gasoline to Helsinge Inc. Once again, Ryan and Ramos appear among the contacts of Morillo and Baquero’s company, this time with the position of “operation analyst.” Lastly, the person designated to sign the document is PDVSA’s vice-president, Chavista Ysmel Serrano.

The PanAm Post sent an email to Helsinge Inc requesting comment, but there was no response. An attempt was also made to contact Ricardo Ramos D’Agostino. Henry Ramos Allup, to whom it was addressed, never replied.

When contacting Vanessa Friedman, the PanAm Post was referred to her attorney. The lawyer assured that for the time being, Friedman could not testify because she is a potential witness in the United States.

**

“It would be a government, which I would preside over, of implacable zeal as far as administrative probity is concerned. If anything must be done in Venezuela with a firm hand, without any hesitation, it is to cauterize once and for all that purulent sore of embezzlement,” Romulo Betancourt said in front of a crowd as he closed his electoral campaign on December 5, 1958.

The documents are as follows:

Above: document of oil purchase between Helsinge Inc and Vitol.

Above: document of oil sale from Helsinge Inc to Petromar.

Above: document of oil sale from PDVSA to Helsinge Inc.

Above: the lawsuit.

Above: statement by Scotland Yard investigator John Brennan

Above: statement by forensic expert John Thackray

Above: email exchanges, banking transactions, and other documents from the Francisco Morillo network.

Versión Español

Versión Español