EspañolThough she left a legacy of poverty, economic stagnation and high inflation, former President Cristina Kirchner still has a following in Argentina.

The latest argument used to defend her has been citing statistics released by the Macri administration that show the economy grew 2.1 percent in 2015. If such an economic growth were true, then there would be no way to claim that the Kirchner administration drove the country toward stagflation — toward that undesirable situation when high inflation and unemployment occur simultaneously. In fact, according to this viewpoint, stagflation would only happen in response to new economic policies.

So is this really what Kirchner was trying to do? Is it true that we were going on the right track and everything changed as soon as she left office?

The key to answering these questions is to consider the big picture, which can put this data into perspective.

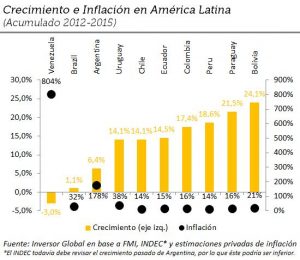

The table below shows the economic growth in Argentina, Brazil, Colombia and the rest of larger South American countries. The left axis shows the accumulated growth between 2012 and 2015, while the right shows the rate of inflation for the same period.

Despite the story some try to tell about Kirchner, the economy in Argentina was at the top for inflation, but near the bottom for growth.

Argentina only beat out Venezuela for inflation. Between January 2012 and the end of 2015, prices in Venezuela climbed to 804 percent. In Argentina, they were less — at 178 percent — which is still considerably higher than the rest of South America, which averaged 21 percent over those four years.

In terms of growth, things aren’t much better. Along with Brazil and Venezuela, Argentina was the country that grew the least over the last four years, with accumulated growth around 6.4 percent — far below Bolivia, Paraguay, Perú or Colombia.

If we look just at averages, over the last four years, the country grew 1.6 percent each year to go with an inflation rate of 29.3 percent annually. It’s not unreasonable to think that Indec, the organization that crunched these numbers, was not overestimating a bit.

Conclusions

These four analyzed years characterize the depth of the populist model imposed by Kirchner. The high fiscal deficit, the persistent inflation, price controls and anti-capitalist discourse did not benefit the good of the people.

In times of political change in Argentina, it is normal for there to be a sense of nostalgia for the old administration. But we should also understand it is not the place we are going to find an answer to our problems.

In fact, it would be better if we took this as a lesson of what not to do while trying to improve the conditions of this country.

Versión Español

Versión Español