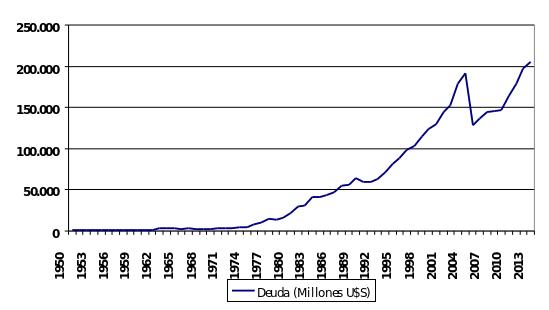

EspañolLike inflation, public debt is still an area where Argentina refuses to learn the most basic lessons. The graph below shows how sharply it has been increasing since the mid-1970s. Thereafter, the debt has grown steadily, except in early 2000, when a drop in total debt had more to do with negotiated write-downs than actually paying back what was owed.

Clearly, debt shows an upward trend, and not a single government in our contemporary history escapes responsibility for this. Perón left the government with a debt of nearly US$8 billion. The military government that succeeded him increased debt levels by approximately $33 billion, reaching an accumulated total of $41 billion. Then, in the 1980s, Alfonsín came to power and debt climbed another $23.2 billion, bringing the total amount to $64.3 billion. In the 1990s, debt increased by almost $59 billion, reaching the $123.3 billion mark. With the presidents that ruled after Menem and before Kirchner, between 1999 and mid-2002, debt increased by $55.4 billion. Therefore, the Kirchner government inherited power with a total accumulated debt of $178.8 billion.

According to the latest data published by the Ministry of Economy of Argentina, total debt as of September 2013 stands at $197.5 billion. This represents an increase of only $18.7 billion in 10 years, and that is the main reason why the current government claims that it has incurred considerably less debt than its predecessors. This wouldn’t be too bad at all, if it were true. The reality is, however, that there is a great deal of unaccounted debt in the government’s figure.

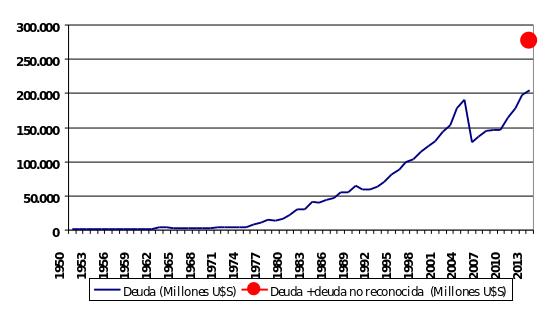

Included in the debt that this government has not accounted for are approximately $12 billion corresponding to 23 trials with the International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID). In addition, there are trials with retirees that amount to roughly $20 billion. There are also pending payments related to the expropriation of Repsol-YPF that total $6.5 billion. Moreover, the holdouts trial could result in additional obligations of up to $15 billion, including payments owed to 8 percent of the bondholders who did not accept a discount agreement and the remaining 92 percent that will only receive a portion of the debt owed. Finally, there is an unaccounted debt of $20 billion coming from the GDP coupon bonds. In other words, if one takes into account the debt that the government of Cristina Kirchner prefers to ignore, the total increases to $277 billion.

This means the debt increase during the Kirchner administrations is actually $98.1 billion, well above the $18.7 that they recognize. This would make the current government the biggest borrower in recent years, even when taking into account the write-downs they negotiated after the 2001 default. The graph below shows the difference between official and private debt estimates, with the blue line corresponding to the official data and the red dot to private estimates for 2013.

Once again, Argentina’s national debt shows a clear, and dangerous, upward trend. It is important to be clear that debt doesn’t just grow spontaneously, on its own, like grass. Debt is a direct consequence of fiscal deficits, a chronic issue throughout the history of Argentina’s public finances, and deficits result from critically high levels of government spending. It’s worth remembering that, during the past 10 years, public spending increased from 30 percent to 46 percent of GDP.

Governments continue to spend the public’s money, accumulate increasingly large debts, and pass it on to their successors. Perhaps we should not spend so much time and energy blaming the vulture funds, and instead concentrate on reducing our chronic fiscal deficit. This is the heart of the problem, and it continues to bury us in a growing mountain of debt.

Versión Español

Versión Español