On Tuesday, the Venezuelan Central Bank and Finance Ministry announced an overhaul and de facto devaluation within the country’s 12-year-old foreign-exchange control system.

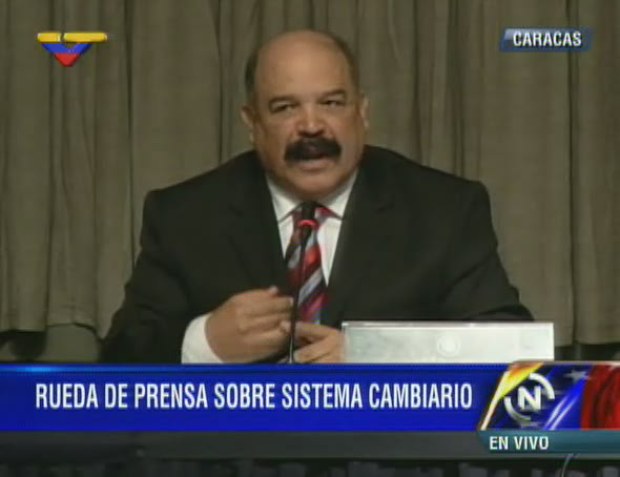

Finance Minister Rodolfo Marco Torres said the lowest rate of 6.3 Bs. per US dollar will remain in place for imports on essential goods, such as food and medicine. However, a single second tier will replace the existing Sicad I and Sicad II rates of 12 and 50 Bs., respectively.

The new rate will start at the price set during Sicad I’s last auction (12 Bs. in November 2014). With both sources of demand merged, though, the price is set to rise soon.

Jesús “Chuo” Torrealba, general secretary of the opposition Democratic Unity Roundtable (MUD), has affirmed this prediction.

2do anuncio:"Las subastas empezarán con una paridad a 12 Bs. X dolar para las demás importaciones,esa tasa se irá ajustando".Ciencia ficción

— Jesus Chuo Torrealba (@ChuoTorrealba) February 10, 2015

“Second announcement: ‘the auctions will start at Bs. 12 per US dollar for the rest of imports; that rate will adjust [itself].’ Science fiction.”

The new unified Sicad is now the rate for the US$3,000 annual allowance per credit-card user for travel and online purchases.

Simadi’s Pivotal Floating Rate

Perhaps most important in the announcement, a third exchange tier was born. Within the Marginal Currency System (Simadi), certain private financial institutions now sell the US dollar “freely” — at the floating or market rate.

While Venezuelan officials have yet to issue the official regulation, this piece of the puzzle has been widely interpreted as an acknowledgment that the black market reflects the real value of the bolívar.

The Maduro administration has explained that the Simadi will not have a fixed rate, and that individuals and firms with dollar-denominated bank accounts will be able to purchase the bolívar at 3,972 authorized stores: exchanges, stock operators, and banks.

Torres explained that the less centralized system will allow Venezuelans living abroad to send money to their relatives, and will encourage trade between sectors that currently can’t get hold of dollars at the official rates.

“The third tier allows the inflow of currency into the country, through operations besides those related to oil, such as remittances and tourism,” added Nelson Merentes, chief of the nation’s central bank.

Simadi will lead to the currency market’s “stabilization,” suiting the needs of the economy, Torres claimed. However, he said the rate will fluctuate within a “margin according to demand” — hinting that it will be a dirty floating exchange, with some intervention from the Central Bank of Venezuela.

The Venezuelan Association of Stock Traders and Association of Venezuela’s Exchanges have both confirmed that the system is ready, but they await the government’s go-ahead.

The Black-Market Rate Now Official?

Venezuelan newspaper Tal Cual reported an anonymous source present at high-level meetings who assured of willingness to let this new tier begin with an exchange rate similar to the underground market. That proved correct, as it opened on Thursday at 170 Bs. per US dollar, more than triple even the highest official rate that has been available (the 50 Bs. of Sicad II).

An estimated daily offer of between $30 and $45 million of dollars will satisfy the demand of individuals and firms, who will only need accounts in Venezuelan financial institutions to participate, claims Tal Cual. However, the same analysts consulted by the outlet warn that the only way to contain a strong demand for Simadi dollars will be with the high rate from the get-go.

Economist Asdrúbal Oliveros told Venezuelan daily El Nacional on Tuesday that the announcements are clearly a devaluation. His reasoning is that the Simadi makes official a much weaker rate, near to the black market’s.

No Rest from Shortages, Inflation

With the merging of Sicad I and II, the migration of private businesses to higher rates is set to hike the prices of products not under regulation or exchange-rate privileges.

Since 2014, the Maduro administration has cut preferential dollars for non-essential imports in half, reports Tal Cual, so firms will have to acquire products from abroad at higher prices.

Economist Miguel Ángel Santos, a researcher at Harvard University’s Kennedy School of Government, holds that the continuation of preferential rates for businesses that import between a third and a quarter of goods into Venezuela will widen the gap in the market’s relative prices. That equates to enormous profits for the privileged, he explains.

https://twitter.com/miguelsantos12/status/565189997234769920

“The real winners are those who will be able to get dollars at [Bs.] 6.3 and 12: by selling them they will earn returns of 1,400 and 2,600 percent.”

OJO que la devaluación NO CREA más dólares: La caída en importaciones, la escasez, la caída de consumo NO se arreglan con dólar libre

— Miguel Angel Santos (@miguelsantos12) February 10, 2015

″Devaluation does not create more dollars: the drop in imports, the shortages, slump in consumption are not fixed with the free dollar.”

Asdrubal Oliveros adds that keeping the 6.3 Bs. rate for food and medicine is a grave error. In his view, this means other raw materials will remain disproportionately expensive, so industries will continue to face losses due to the low income available for their products.

The business sector, for their part, have requested the abolition of all controls on the national currency’s value. In an interview with national TV station Globovisión, the vice president of the Venezuelan Federation of Chambers of Commerce, Francisco Martínez, said on Tuesday that the currency controls should be eliminated “gradually, and before monetary and fiscal-adjustment measures need to be taken.”

On February 5, Venezuela’s currency control system turned 12 years old, during which seven devaluations took place. According to Santos’s calculations, the government has depreciated the bolívar 32,900 percent, at an annual average rate of 46 percent.

Translated by Daniel Duarte. Edited by Fergus Hodgson.

Versión Español

Versión Español