EspañolConfidence in the judiciary may not go hand in hand with Latin America, but two new reports say the region’s courts are getting worse, not better. “These reports can serve as warning signs to the governments and people of Latin America,” says Lisa Rickard, president of the Institute for Legal Reform (ILR).

Last week, her organization, a wing of the US Chamber of Commerce, published “Following Each Other’s Lead: Law Reform in Latin America” and “Class Action Evolution: Improving the Litigation Climate in Brazil.” Prepared by Shook, Hardy & Bacon, both examine the heightened tendency of courts to favor class-action lawsuits in 13 countries of the region, and the broader impact on their judicial and economic integrity.

New policies, Rickard claims, are set to accentuate the problem: people should “guard against misguided legal avenues that could turn into highways to abusive litigation.… If implemented, current proposals could have costly, unintended economic consequences for many Latin American countries.”

At the release, ILR warned that legal reforms on the table in countries such as Argentina, Brazil, Ecuador, Mexico, and Costa Rica would “hand power over to outside groups to head class action lawsuits and in many cases even compensate them.” Further, ILR claims that safeguards against frivolous cases are disappearing, amid what the institute characterizes as a well-intentioned quest to provide access to justice that fails to account for economic consequences.

Economic Incentives Perverted

The report cites the case of Colombia, where the 1998 Popular Action Law sparked a wave of litigation. If the case proved successful, the legislation granted the “popular actor” — who represented and directed the case for those affected — financial compensation, “in some cases a percentage of the value of the claim, which could be big money.”

This spawned a cottage industry of professionals. In 2010, these professionals filed over 20,000 of these “popular action” claims. Even out-of-court settlements, the report claims, only fast-tracked the returns and multiplied the claims. Later that year, under the weight of cases, the Colombian legislature reversed the financial-compensation element for the third-party representatives.

The particular compensation, ILR asserts, can “disregard the true interests of plaintiffs and … distort justice by incentivizing the filing of baseless claims and undermining basic fairness and due process.”

Initial Acceptance the Tipping Point in Broader Shift

ILR also identifies the regional effort to reduce scrutiny over newly filed claims, the admission stage, as the precise point of concern. This opens the door, they say, for a larger quantity of unjustified claims.

The report mentions Chile, where delayed processing received heavy criticism. In 2008, claims had been backed up since 2004. Of the 40 presented at that time, the majority were simply dismissed, and only one has gone to trial, where it remains pending.

In 2011, the Chilean legal process saw reform and an abbreviated admission stage. In some cases, the new legislation eliminated the admission stage altogether. In particular, numerosity and superiority were no longer requirements.

This means “a class action can have as few as a handful of claimants, and they need not demonstrate that a class action device is superior to individual lawsuits as a means to adjudicate the claims.”

On the other hand, in Argentina, the right to initiate a collective case exists expressly in the 1994 constitution and the Law of Consumer Protection. However, no law or procedure exists to establish the legal process to present a claim, even though the Supreme Court of Justice requested one in 2009 and in 2013.

In the absence of a clear law for the process of collective claims, consumer law allows for a “brief process” to take place. Within that prevailing convention, the defendant is limited to five days to prepare his defense, something that the ILR views as unfair.

The “Following Each Other’s Lead” report asserts that the heightened use of collective claims and direct petitions to national supreme courts, against private parties, is part of of a tendency which is evident throughout Latin America.

“Plaintiffs use the Amparo as an adjunct to civil litigation … without litigating against the real target of their claim. If a family wants to stop a construction project near their home, they can file an Amparo… This is a claim solely against the government, using an abbreviated process, seeking a decision that the construction violated a constitutional right.”

The report also states that this is acute to Latin-American nations. They point out that the United States does not have the direct, streamlined protection of the Amparo.

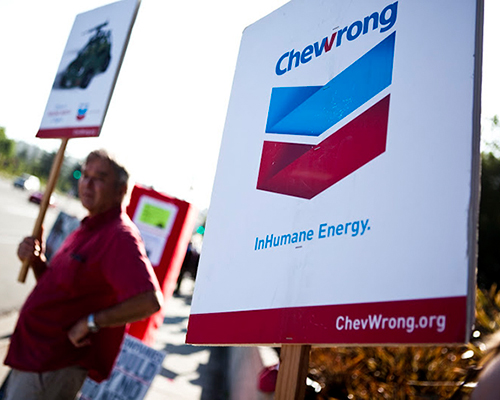

Chevron: A Legal Mess in Ecuador

On February 14, 2011, the Provincial Court of Sucumbíos in Ecuador ruled against Texaco (now merged into Chevron) for polluting areas where it operated with Petroecuador between 1964 and 1992. The court ordered Chevron to pay US$8.6 billion in damages, plus $860 million (10 percent of the damages) to the Amazon Defense Coalition.

This ruling came from the María Aguinda vs. Chevron class action lawsuit, which, according to Chevron, was financed by hedge funds and speculators who stood to benefit from a guilty verdict.

Steven Donziguer led the group of lawyers who claimed to represent 3,000 indigenous people of the Amazon rainforest. However, there were only 48 official plaintiffs in the case, and Chevron alleges that the signatures were forged. The company also maintains that the lead plaintiff in the case, María Aguinda, did not understand the lawsuit and signed the court documents to get free medical care.

The counterargument, from “Amazon for Life,” is that the damage caused by Texaco amounts to a “Chernobyl of the Amazon” and affected over 30,000 people: “Today, dozens of communities continue to suffer the consequences of pollution affecting their health… Several indigenous communities in the area have had to leave their traditional homes.”

The legal wrangling that unfolded in US courts to some degree vindicated Chevron — at least in so far as Ecuador’s judgment against Chevron was the product of fraud. A US District Court in New York ruled in March that Donziguer had engaged in wiretapping and money laundering, among other charges.

The final outcome may rest with the Permanent Court of Arbitration at the Hague. Since 2012, the oil company and the Republic of Ecuador have been in dispute there.

Regardless of the outcome, the extremely expensive Chevron case has been a banner for the problems associated with collective claims, particularly those initiated by outside parties. The ILR warns that this unpredictable environment contributes to economic instability and reluctance on the part of investors towards Latin America.

James Craig, Chevron’s communications advisor, told the PanAm Post that “Today there are not sufficient conditions for our company to be interested in investing in Ecuador. But we feel that our case teaches a lesson to investors … that they take into account when they are considering investing. Clear rules, transparent forums, free of political influences, are important, and that has not been the case with Chevron in Ecuador.”

Versión Español

Versión Español