By Diego Sánchez de la Cruz

This year marked a turning point for Latin America. After a long period of socialism, the political events we have witnessed in the last 12 months seem to be inviting us down an optimistic path toward freer days.

Cuba dictator Fidel Castro is dead. Venezuela President Nicolás Maduro is becoming a pariah before the eyes of the world. Ex-President Dilma Rousseff was dismissed.

Moreover, the popularity of Chilean President Michelle Bachelet has reached historic lows. Ecuador President Rafael Correa announced he will not run for president again. Colombians spoke up about the FARC peace deal and Peru’s new President Pedro Pablo Kuzcynski conquered the government in the presidential elections.

The Heritage Foundation just published a report that puts these events into perspective. Authors James Roberts and Sergio Daga predicted a pro-liberty turnaround for the region.

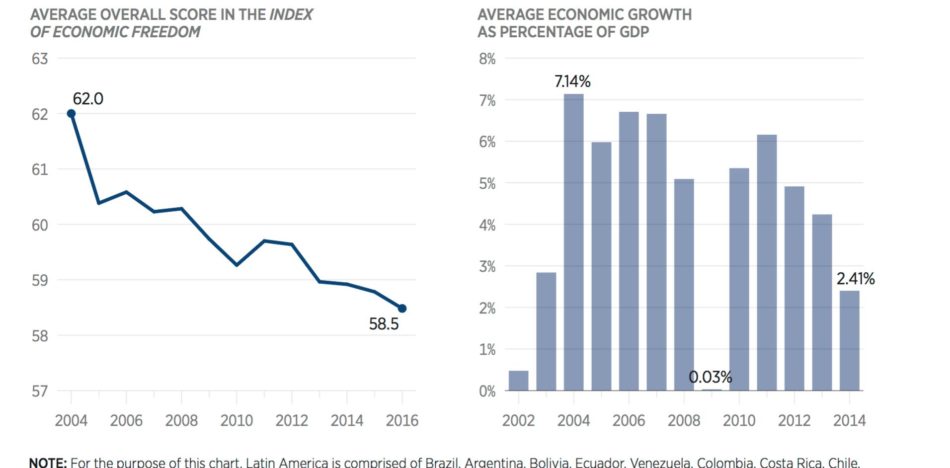

Since 2004, the average score of Latin American countries in the Index of Economic Freedom in the World has decreased from 62 to 58.5, in contrast to the increase in Asia and Africa. The socialist period has slowed the advance toward market economies, resulting in a loss of competitiveness for the whole region.

The result is already noticeable. Heritage recalled that regional GDP growth surpassed seven percent in 2014 but, despite the commodity boom, a steady decline in growth levels has characterized the last 10 years — so much so that some of the greater economies of the region, such as Brazil, have entered into recession.

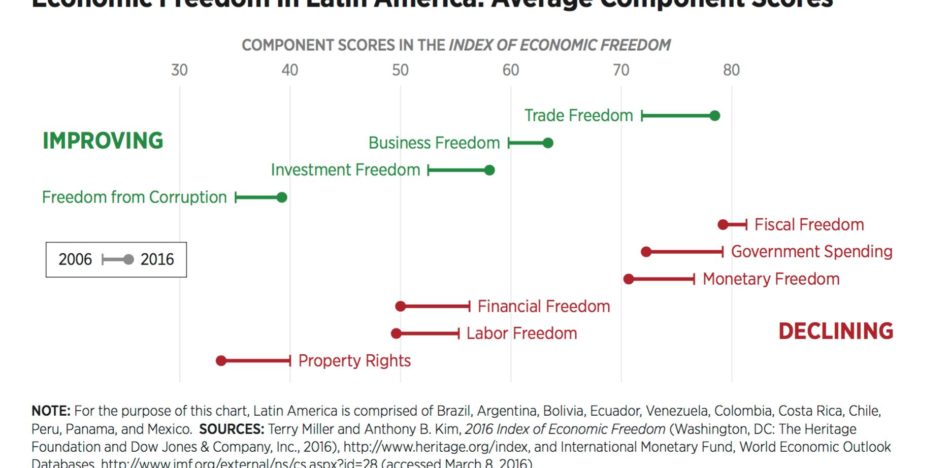

What elements of the Index of Economic Freedom have worsened? Roberts and Daga assert there has been an increase in public spending and taxes, deteriorating monetary conditions, less financial freedom, a lower degree of labor flexibility and a worse situation regarding the protection of property rights.

On the contrary, there have been slight improvements in the fight against corruption, openness to foreign investment, ease of doing business, and trade integration with the rest of the world. But these advances are short in comparison to the rest of the world, leaving Latin America worse than it was a decade ago.

Looking ahead, what will the end of socialism mean for Latin America? Between 2016 and 2020, the region is predicated to grow at an average of 1.75 percent. However, those countries that have been laying the foundations of a model of economic freedom will develop at a higher rate, whereas the countries where the interventionist model is collapsing present negative perspectives.

Thus, while Venezuela will see its real GDP fall at a rate of 3.6 percent, Chile, Mexico and Colombia are expected to grow between 3.1 and 3.5 percent. The absolute leader, of course, will be Peru, which is expected to grow at 4.5 percent over the next four years.

Hopefully, the excellent growth figures that the countries with the most open economies in Latin America expect will help to accelerate political changes in those places where socialism has left a legacy of decline, populism and corruption. The bad news that we find every day reminds us that there are many challenges ahead, but it is worth looking back to see that, fortunately for us, the interventionist positions are weaker these days, and the pro-liberty discourse is making its way in the region.

Versión Español

Versión Español