EspañolOn Monday, the government of President Cristina Kirchner announced a three-month extension for a tax amnesty program, in effect since July of 2013, in an effort to repatriate foreign currency held by private citizens abroad.

She confirmed the extension through the Official Gazette on Tuesday morning, justifying it by saying that “a greater number of individuals or entities are able to disclose their holdings and take advantage of the benefits provided in Law No. 26,860.”

The law was supposed to bring US$4 billion into the country during its first three months, but after nine months it has only managed to attract US$754 million — 18.8 percent of the government’s initial goal when Kirchner urged Congress for its immediate approval.

The idea was that after bringing currency back into the country, owners would voluntarily declare so and this would help stabilize the financial situation. Moreover, the government sought to use idle resources (idle from the point of view the state, not of the individual who saved the funds) to finance productive investments for the economic and social inclusion of various sectors of society.

In an economy with an official monthly inflation rate of 3.4 percent, and a regime of exchange controls, the Argentinean government sought to entice savers with Law No. 26,860. It allows the disclosure of funds held overseas without specifying their source, thus waiving the payment of many taxes that would otherwise apply.

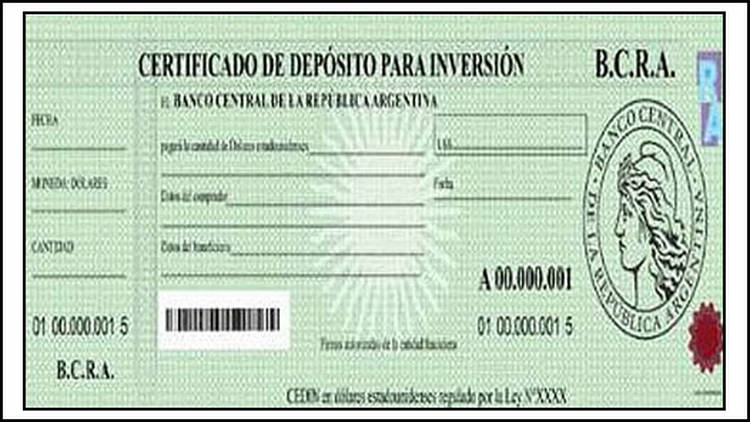

For the repatriation of funds, the depositor must use any of two financial instruments launched by the Ministry of Economy, both valued at the official US-dollar exchange rate: the Certificate of Deposit for Investment (Cedin) or the Argentinean Savings Bond for Energy Development (Baade).

As detailed in Article 2 of the law: “The Central Bank of Argentina is hereby authorized to issue the ‘Certificate of Deposit for Investment (Cedin),’ in US dollars, which is identifiable and transferable, constituting a suitable medium for the cancellation of debts denominated in US dollars, and whose financial conditions shall be established by regulations of the Central Bank of Argentina.”

The Cedin was designed as an investment vehicle to revive the real estate and construction sectors, both deeply affected by the exchange controls. On the other hand, the Baade was intended to finance investments in the energy sector — lacking investments for years and constituting a key problem for the country’s public finances — with a special focus on investments in the nationalized oil company YPF and its Vaca Muerta field.

The Failure of the Tax Amnesty

Lawyer and financial analyst Carlos Maslatón explains that there are several factors that account for the failure of this measure. He told the PanAm Post that the measure “was designed by Guillermo Moreno [former Secretary of Commerce] at his worst moment, with the black market exchange rate going through the roof, which generated no credibility.”

He says that another cause for the failure of Cedin up to this point could have been that opposition members of parliament are not going to accept it when Kirchner’s mandate ends. Finally, Maslatón explains that if someone transfers the money into the country from an unreported bank account held abroad, he must report its history of transactions.

This will be the third time the executive has extended the policy of voluntary disclosure of foreign currency holdings. They continue to use the same financial instruments that did not work in September or December last year, and as some experts predict, will not work in April this year. In December, only US$570 million had been raised.

Jorge Oviedo, a journalist for La Nación newspaper, wrote that a “government that forbids savings in US dollars asked us to exchange them for a certificate of deposit. Was there any reason to not trust the government? There were many, the first being that the administration itself had already broken many promises.”

The economy minister himself explained that this measure seeks to attract dollars into the country to reintroduce them into local production. However, as economic analyst Iván Carrino from the Liberty and Progress Foundation of Argentina in El Cronista newspaper warned before the end of the first period, only a few adventurous ones would do such a thing. In the words of Carrino, “Who would be willing to bring back their savings into the legal circuit when they already got what they wanted, which was precisely to steer them away from it as much as possible?”

Versión Español

Versión Español