Under the bland name of “Argentina Digital,” Congress passed on December 16 early morning a legislative proposal that will extend the clutches of the state into telecommunications. From postal services to telephones, including internet content, the proposals by the government of Cristina Kirchner aspire to the control of all methods of communication.

The Minister of Federal Planning, Julio de Vido, spelled it out when he unveiled the initiative: it guarantees “a human right to telecommunications.” But after the announcement of the creation of a human right, greater state intervention inevitably follows. If the norm is fully implemented, it could return Argentina — in technological terms — to the nineteenth century.

The government will have the power to fix the price of all information and communication technology.

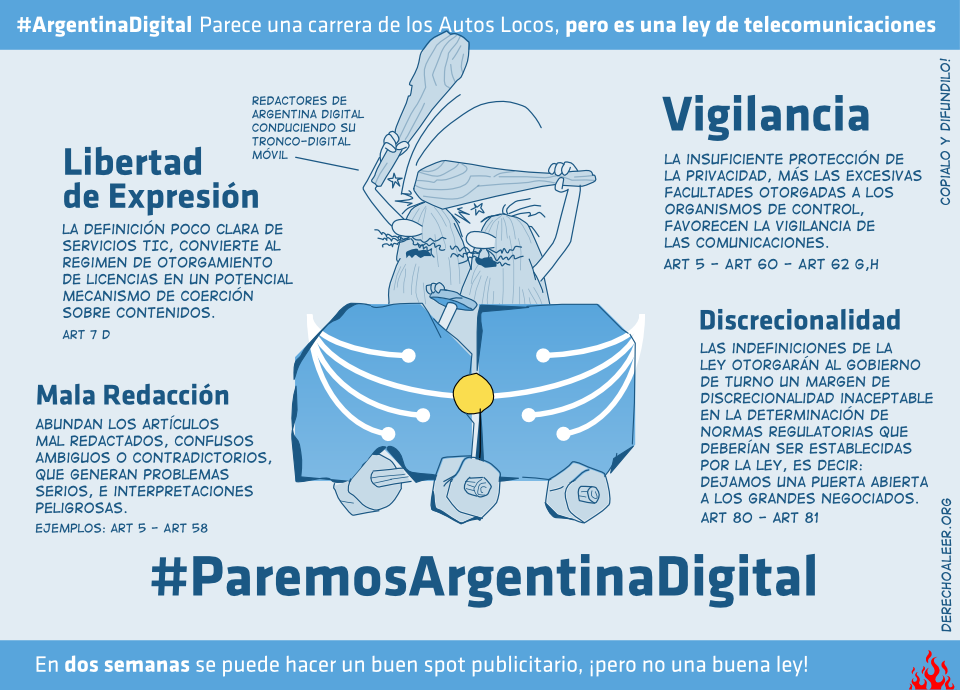

This legislation reflects the way in which Argentina has been ruled throughout its history. Argentina Digital sees the executive delegate almost unlimited regulatory power over telecommunications to a commission picked entirely by the government itself. Its powers, broad-ranging and ambiguous, openly invite abuse.

As proposals stand, the government will have the power to fix the price of all “information and communication technology,” a loose concept which fails to establish clearly which services are affected. Argentina Digital will place new burdens on service providers, increasing the bureaucratic demands made of them, and, above all, will put privacy and liberty of expression in danger.

Paranoia and Privacy

For example, according to article 65, the all-powerful Federal Authority of Information and Communications Technology (AFTIC) will be able to interrupt a service if it deems it to be in the interests of the malleable concept of “national security.”

In another instance, article 5 proclaims the “inviolability” of communications, requiring a judicial order for their “interception” and analysis. Yet authorization from a judge would not seem to be necessary for “passive observation, analyzing data traffic, or geolocation,” other methods of monitoring, argues Enrique Chaparro of Fundación Vía Libre.

Furthermore, the law doesn’t limit itself to the digital world. It even leaves the privacy of the home open to state interference. Among the obligations that the law imposes upon ICT users is to “permit the access of the authorities to their personal information and applications. Users should be duly identified of the results of any kind of operation or necessary verification.” The government is thus discarding the “inviolability of the home” safeguarded in the national Constitution, and hiding one of the most controversial elements among mountains of text.

Believing that government powers should be clearly limited is only considered paranoia until the state begins to violate citizen rights.

When I made this point to friends, many called me paranoid. “It’s understandable that they put this article here,” they told me. “Unless you think that they’d raid people’s homes without judicial authorization?” Maybe they’re right. To believe that the government would invade the homes of millions of Argentineans using this article might sound crazy.

However, believing that government powers should be clearly limited is only considered paranoia until the state begins to violate citizen rights. Laws should be mapped out as if it were the worst people who will apply them, for those who govern us are surely no angels.

License to Block

A key aspect of the proposals is the system of licenses, which represents a serious threat to freedom of expression. In the same way, the media law — passed in 2009 — uses a licensing system to authorize or deny the development of new communication companies, keeping critical media under government control by constantly threatening to revoke their license.

The incoherent terminology used, particularly in defining what constitutes information and communications technology, leaves the door open for private networks having to pay to obtain a license to operate. The law could compromise video services like Skype or Google Hangouts. The new regulations will allow the government to interrupt and deactivate these applications — proven to have facilitated coordination of protests and other democratic opposition initiatives elsewhere — whenever it suits them.

Argentina is among the worst countries in the world when it comes to internet access. According to the State of the Internet report, the South American country ranks 41 out of 56 with regard to internet speed, with an average transfer speed of 3.2 megabytes per second (Mbps) lagging behind a global average of 3.9 Mbps. This dismal picture is the result of a decade of negligible incentives and guarantees necessary for investment. In real life as on the web, the arbitrary state is the enemy to the successful operation of the market.

This latest proposal will only repel investment even further, compromise quality, and end up sinking a sector which is already on the edge of collapse.

Versión Español

Versión Español